Zita Amwanga, GPJ DRC

Supporters of presidential candidate Emmanuel Shadary parade through Kisangani, a key city in Democratic Republic of Congo in November. Shadary was hand-picked by current president Joseph Kabila.

Voters in Democratic Republic of Congo had been waiting for a chance to cast ballots for years before polls finally opened, at least in some parts of the country, on Dec. 30, but results haven’t been announced yet and it’s not clear when that will happen.

This election, in which Congolese voted for a new president, was originally scheduled for 2016. President Joseph Kabila, who has been in power since 2001, repeatedly delayed voting, a move widely criticized by human rights agencies and other governments. By August, when Kabila announced that he would not seek another term as president, analysts and many Congolese worried that the election would somehow be rigged to ensure that he remain in power, even if not as president.

The election was initially set for Dec. 23, but it was delayed in part because a warehouse fire destroyed some of the electronic voting machines that many Congolese feared would invite tampering. While polls opened throughout most of DRC on Dec. 30, they remained closed in some areas – a move government officials say was intended in part to protect people from an ongoing ebola outbreak, which has wracked sections of eastern DRC.

When polls closed, the government shut down the internet in some areas, stating that it would be restored after the release of election results, originally scheduled for on Jan. 6.

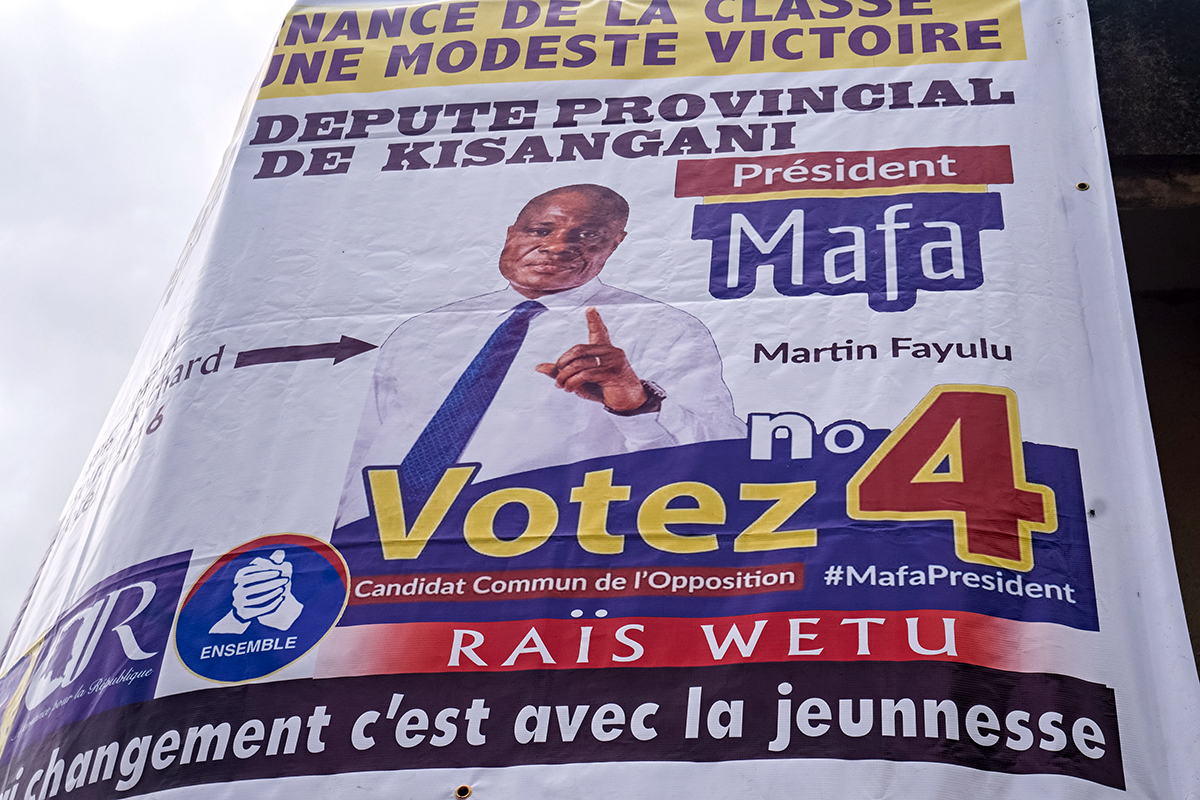

According to a report published in December by Congo Research Group, Martin Fayulu, the leading opposition candidate, was expected to take 47 percent of the vote, compared to 19 percent for Emmanuel Shadary, Kabila’s hand-picked successor.

While politicians bicker over the election and voters steel themselves for potential violence over what will happen next, daily life in DRC is fraught with chronic cronyism, crumbling infrastructure and poverty.

Across the country, students struggle to study in schools that aren’t equipped for basic use. Roads become so muddy during rainy season that travel, even to transport critical supplies, becomes nigh impossible.

The country’s breathtaking natural resources aren’t well-managed, and locals who head to mines to earn a living wind up working in dangerous – even deadly – conditions. Efforts to improve civil institutions, including a judicial system to protect ordinary people, often stall. Violence is endemic across broad swaths of the nation.

But there are bright spots, too. Farmers in a rural section of North Kivu province say they’re earning money from their world-class coffee crops. Friends and families celebrate weddings and activists pursue wildlife conservation. Citizens find their own community-based solutions to fulfill basic needs.

No matter the outcome of the election, life in the often-isolated communities that make up this country, many of which are far from the capital of Kinshasa, will continue, as it always has.