POINT PEDRO, SRI LANKA — As rays of morning sun scatter on the sea, Amirthanathan Rgeraj lands his small boat and fills a basket with his catch. He has spent half of his 40 years repeating this scene. But in the past year, not a day has passed without him wondering if his last day of fishing might be near.

“What I felt in that situation can never be put into words,” he says of the event that triggered his worries. “I felt as if my life was over.”

Amirthanathan says that a year ago, he went to pick up nets he had cast the night before to catch stingrays. He was shocked to find that half of his nets, worth 300,000 Sri Lankan rupees ($838), had been damaged by what he suspects were Indian fishing boats. Since he lost his equipment, Amirthanathan says his monthly income, which averaged around 120,000 rupees ($335) before June last year, dropped to 30,000 rupees ($84) the following month and has stayed low since.

Thousands of northern Sri Lankan families that rely on fishing are struggling to maintain their livelihood, which they say has been severely impacted by their Indian counterparts, whom they accuse of fishing illegally in Sri Lankan waters and using methods that damage local fishermen’s nets. Sri Lankan fishermen, who use traditional methods, also accuse the Indians of bottom trawling, a method they say is depleting fish stocks.

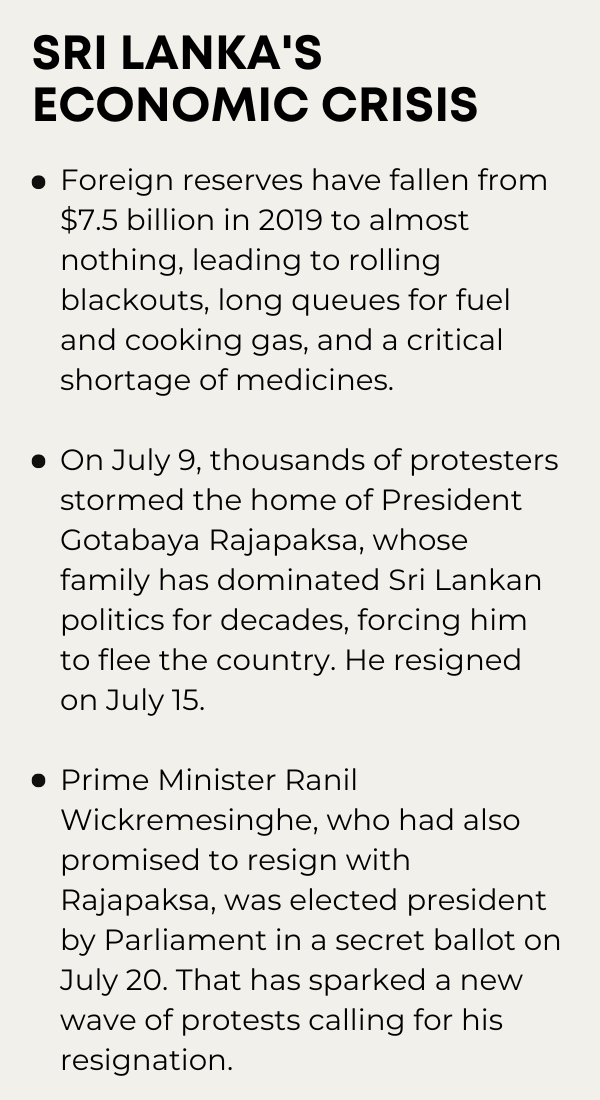

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, which has led to a severe countrywide shortage of fuel, has worsened the situation in the fishing sector. Many fishermen are out of business due to a lack of boat fuel. The crisis is likely to be prolonged after thousands of protesters stormed the presidential palace in Colombo on July 9, forcing President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to flee the country and resign. Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, who had also promised to resign with Rajapaksa, was elected president by Parliament, sparking a new wave of protests.

Marine fishing is the main livelihood of 50,310 families in the Northern Province of Sri Lanka, and more than 200,000 people in the region depend on income generated by the industry, according to a 2020 report from the Ministry of Fisheries.

A 2021 joint study by Sri Lanka’s National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency and the University of Ruhuna cited a report showing that Indian fishermen encroached on Sri Lankan waters at least three times a week. Annalingam Annarasa, president of the Jaffna District Fishermen’s Cooperative Society Unions Federation, alleges that Indian fishermen loot marine resources worth an estimated 1 trillion rupees (about $2.8 billion) a year.

“This is economically hurting Sri Lankan fishermen, who fish using traditional methods,” Annalingam says. “The struggle of local fishermen will continue against the encroaching Indian trawlers and local trawler industry that is destroying the marine resources of Sri Lanka.”

Overfishing in the Palk Strait, which separates Sri Lanka and India, has led to the extinction of some nonmigratory fish species, says Kanapathipillai Arulananthan, the principal scientist at the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency.

The roller method, also known as trawl folding or bottom trawling, involves attaching an iron chain or bar to both ends of a net, which sinks it to the ocean floor. A tugboat then drags the net to catch fish. Trawl fishing is legal in India, but Arulananthan says Sri Lanka banned it in 2017 because studies found that it was destructive to the marine environment. The Sri Lankan government put enforcement of the ban on hold to allow local fishermen enough time to transition to traditional methods, he says. Fishermen using the method are required to obtain permission to fish only in certain seas off the coast of Sri Lanka.

Coral reefs and marine vegetation, which provide breeding grounds for fish, have been destroyed by the roller fishing method, he says. “Sri Lankan and Indian ecologists and scientists should work together to come up with a solution by exchanging data on how the marine environment will be affected if fishing is done continuously by this method.”

Traditional fishing uses various nets and baits, and equipment to find out which species of fish are available at what time and place. This allows the fish to breed and thrive in areas other than the fishing grounds. Marine biological balance is not affected.

Sri Lanka’s minister of fisheries, Douglas Devananda, says he is in talks with top Indian government ministers to set up a joint working group comprised of marine workers and researchers from the two countries to address the issue. But he says Sri Lankan authorities will continue patrolling the waters to arrest Indian fishermen who cross the maritime boundary and destroy equipment.

“If they violate our waters, we will arrest them and take legal action,” he says.

When reached by telephone, Anitha Radhakrishnan, the fisheries minister of Tamil Nadu, India, declined to respond to accusations against fishermen from his country. But in February, India’s minister of state for external affairs, V. Muraleedharan, released a statement saying that the Sri Lankan navy arrested 159 Indian citizens in 2021, compared to just 74 in 2020. Between 2010 and 2021, 3,680 Indian fishermen were arrested in Sri Lankan waters, according to data from the ministry.

NJ Bose, state general secretary of the Tamil Nadu Mechanised Fishermen Welfare Association, says his organization urges Indian fishermen not to fish in Sri Lankan waters. He also says that the marine area between the two countries is very narrow and that the problem has escalated as Indian fishermen have been using prohibited nets in Sri Lankan waters. “I’m the biggest enemy of trawl nets here,” he says.

Sri Lankan fishermen, whose families have been in the industry for generations, now say they are not sure they can afford to continue fishing. Nakarasa Varnakulasinkam began going to sea with his father 49 years ago, when he was 11. The government’s failure to end the banned fishing practices worries him. “Our next generation will not be able to do this business,” he says.

Nakarasa’s oldest son, who fishes with him, has wondered if he should find a job that pays wages. His youngest son, who is in 10th grade, has already decided that he wants to study so he won’t have to “suffer like us.” Nakarasa says he blames both Indian and Sri Lankan trawling boats for depleting resources, and calls on the government to stop issuing permits and instead impose a total ban on trawling.

While acknowledging that the tugboat industry is detrimental to marine resources, Arulananthan, the National Aquatic Resources Research and Development Agency scientist, says it’s not fair to compare Indian and Sri Lankan tugboats. “Indian fishermen use six-cylinder tugboats with a massive force, while Sri Lankan fishermen use two-cylinder ones,” he says.

He also says that the nets confiscated from Indian fishermen have very small holes, which catch fish indiscriminately.

Since trawlers destroyed Amirthanathan’s nets, he has had to switch to bait fishing to earn a living. This doesn’t require leaving nets overnight in the sea. Fishermen stay on a boat, wait for fish, and leave with their nets when they’re done. But the method is expensive because he has to buy bait for between 10,000 and 15,000 rupees ($28-$42) each time he goes out to sea. Because marine resources have been depleted, Amirthanathan says he now has to travel up to 25 kilometers (15 miles) from shore to catch the same amount of fish he used to catch within half that distance 10 years ago. He’s not sure what he would do if his business doesn’t survive.

“I have already used all my savings,” he says, “and even pawned my wife’s jewelry to start over.”

Thayalini Indrakularasa is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Vavuniya, Sri Lanka.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Lohith Kumar, GPJ, translated this article from Tamil.