Prologue

This is a story about home.

It’s about my home, a little town called Kirumba in the heart of Democratic Republic of Congo’s embattled North Kivu province. You may have never heard of this place. Foreign journalists don’t come here. I am the only reporter here.

The story of my place is little understood. In my lifetime my home has been a peaceful sanctuary and an emblem of war-torn chaos. My little corner of DRC produces thousands of global refugees every year. Millions more are internally displaced too.

This is the story of why so many people go. It’s also the story of why I will always stay.

I’m sharing my memories with you because I believe we have more in common than you think. I’m sharing the history of my homeland with you, because I want it to be more than a place you associate with tragedy.

Welcome to my home.

Chapter 1: Recollection, 1996

“A date I’ll never forget.”

This tiny village, the place where my family is rooted, sits in a valley surrounded on all sides by mountains. To the east of the village is the Taliha River, which sends its breeze across the village each morning and again in the evening, when the sun’s light mellows into an evening glow. The rustling of the banana and coffee trees – psithurism, as we call it – sounds romantic.

When the wind picks up and knocks branches from trees, we are fearful. The thud of those branches reminds us that an enemy might come and strike us hard. We have no choice but to remain alert, watchful.

At the time of this memory, more than two decades ago, most of the homes in Hutwe were made from straw or mud. When it rained, water dripped through the thatched roofs. We covered ourselves with plastic to stay dry.

I can still smell the banana leaves, and the goat dung from nearby sheds. And I remember how my grandfather used to say to me, “Don’t be scared. If the enemy comes in, we will run away. We will hide in the caves.”

His village was my place of refuge when I was a child. I lived in Kirumba, a rural town 37 kilometers (about 23 miles) away, but my grandparents lived in Hutwe, where my family has land.

I was 17 years old in 1996. That year, the national army clashed with the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL), a group led by Laurent-Désiré Kabila, who would soon become president.

The fighting was in South Kivu province – hundreds of miles away.

That left the Wangilima, a pro-Kabila armed group, free to roam in Lubero territory, the region where I live.

Lubero territory had always been isolated. For the most part, people stayed put, and outsiders didn’t come in. But when tens of thousands of Hutus from Rwanda pushed across the border into DRC, fearing retaliation for the genocide that had just occurred in their own country, they were met with violence here, too.

The Wangilima stormed Kirumba in March of that year, hunting for anyone who spoke Kinyarwanda or who was suspected of being Rwandan. They jumped at the chance to realize a grisly plan to exterminate them, even if their brutal methods also killed some Congolese people.

Our village chiefs continually negotiated with them to stop killing our people and let us work in our fields. But those negotiations made life tense. We lived with the Wangilima at our throats for months.

Things got even worse a few months later.

The AFDL – the group led by Kabila, who was vying to wrest the country from then-President Mobutu Sese Seko – pushed through the area, using heavy artillery to exert its power and expel Rwandans. It didn’t matter that we, and so many others, were Congolese. The Banyarwanda – people of Rwandan descent living in what is now eastern DRC – lived among us.

We went on the run, fearing for our lives.

This is a date I will never forget: July 4, 1996. It was just after 5 a.m. Heavy shelling and rocket fire came from the Mighobwe and Bwatsinge hills, 7 kilometers (4 miles) to the north. There was thudding all around.

We had never experienced this before. I asked my mother to tell me what was happening. She didn’t know.

Outside, people ran in all directions. Mothers held babies in their arms. Bare-chested men fled. We could hear people screaming and crying. Everything was in chaos. Suddenly I couldn’t find my mother or father. My two little sisters – Oripa, 13, and Rachel, 11 – and I had no choice but to run to Hutwe on our own.

Traveling such a great distance on foot was something I hadn’t done before. One day wasn’t enough for the journey. We slept that first night in an abandoned hut on Itungi, a hill located a few kilometers away.

That night, intense shooting erupted again.

We ate raw cassava, slept and early the next morning walked some more, this time in torrential rain. We weren’t alone by then. Huge numbers of people were en route to Hutwe.

When you don’t know when you’ll get home again, you carry your home with you. Everyone had loads on their heads.

The mountain paths were slippery. We looked like hogs that had rolled in the mud because we struggled to stay on our feet.

When we reached Hutwe at 4 p.m. the next day we found a happy surprise: Our parents were there.

It was a joyous reunion; we didn’t have much hope of seeing each other again.

The people who lived in Hutwe watched over us. They knew they might be in the same situation one day.

The village didn’t have much. We ate the local harvest of yams, pumpkins and bananas, but there were too many people vying for the food. We slept on dry banana leaves with empty stomachs in my grandparents’ home.

Soon, we had health problems: diarrhea, influenza and early signs of chronic hunger. My youngest sister, Grace Kyakimwa, suffered most of all from malnutrition. She was just 4 years old at the time.

So, my family decided it was time to return to Kirumba, even if the Wangilima might kill us.

“Living away from our home and fields was the worst nightmare I’ve ever had as a father,” my father told me when I asked him to recall the memory.

But we paid a literal price when we chose to return to Kirumba. The AFDL forced people to hand over cash to buy a ceasefire, however tense.

Some families tried to sneak back into the village without paying, but they were severely beaten when they were caught. As they pummeled the bellies of those people, the soldiers said they were “warming their intestines.”

My father remembers that he paid 10,000 Zairean zaires to secure our reentry. (In May 1997 my country changed its name from Zaire to Democratic Republic of Congo.) That amount of money was worth a fraction of a cent when compared to the U.S. dollar, even at that time. International economists had dismissed the zaire as worthless, but in isolated Kirumba, 10,000 zaires bought passage for my entire family to return to our home.

My parents were ready to accept any condition to get back home.

Chapter 2: History

The Roots of the Conflict

DRC has the twelfth largest land mass of any country in the world. Large sections of the country are isolated. According to the World Population Review, roughly 86.6 million people live here.

The country reaches across the center of the continent and claims a huge portion of the densest forests on earth. It is dotted with tiny communities connected only by footpaths.

This is the part of the world that spurred Henry Morton Stanley, the British adventurer, to designate Africa “the darkest continent,” a phrase that simultaneously sparked the imagination of colonial treasure hunters and popularized the notion of a homogenous place filled with treacherous jungles, powerful wildlife and unsophisticated people. Stanley’s accounts of the area that is now DRC effectively opened the territory up to European exploration – and exploitation.

Belgium’s King Leopold II claimed what is now DRC in 1885, 16 years after Stanley began his adventure there. Initially, he ruled it as his own private business venture.

Those years under Leopold II were crushing for ordinary Congolese people. More than 10 million people were killed. Alice Seeley Harris, a British missionary, publicized the grisly practices of the Anglo-Belgian India Rubber Company in particular, which enslaved Congolese people and mutilated or killed them and their children if they failed to meet their rubber harvest quotas. Harris’ photographs brought international attention to Leopold II’s privately held state, which ultimately forced him to hand it over to Belgium, the country he ruled, in 1908.

Belgium relinquished control entirely in 1960, when the country gained independence.

But the exploitation continued. DRC is rich with diamonds, gold, cobalt, oil and other natural resources. Local armed groups and major international mining companies operate there with relative autonomy because there’s little oversight. Here, the most resource-rich areas are the ones that are also the least-developed.

The fate of people in eastern DRC is inextricably linked to what happens in neighboring Rwanda.

When the genocide in Rwanda ended after about 100 horrific days in 1994, over half of the 2 million Rwandans scrambling across the border fled into eastern DRC, still called Zaire at the time. They feared that the new Tutsi-majority government would seek revenge for the Hutu-led slaughter of 800,000 or more people. Many of those refugees were ordinary people who worried that their Hutu tribal identity would mark them for death; but tens of thousands of them hoped to revive armed groups in refugee camps. By mid-1996, refugee camps in DRC’s North and South Kivu provinces, while technically run by the U.N. and other organizations, were controlled by armed groups with allegiance to the Hutu-dominated Rwandan Armed Forces, which played a key role in carrying out Rwanda’s genocide.

The Wangilima that controlled Kirumba in 1996 claimed that they wanted to push the Banyarwanda out of the area, but they took advantage of the town’s isolation by threatening the people with violence. When the AFDL came, it was the same. Kabila, their leader who was supported by Rwanda’s new government, sought to expel anyone with Rwandan roots from the country, whether a newly-arrived refugee or someone who’d been there for decades. And in that case, too, vicious violence was applied liberally, no matter a person’s ancestry.

Chapter 3: Recollection, 1994

“I remember the first time I saw refugees.”

I heard no gunfire in 1994.

It wouldn’t be true to say that everything was golden in those days, but at least we had peace. Most people here focused on farming: cassava, beans, corn, millet, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, Irish potatoes. Some grew bananas to make a local beer known as kasiksi.

According to my memory, life felt blissful. Some people, especially those involved in politics who were frustrated by President Mobutu Sese Seko’s regime, fled to other countries. But for us ordinary farmers and livestock keepers, we tilled our lands without fear. Absence of war was all we needed.

I remember the first time I saw refugees. It was 1994 and I was going to Kayna General Hospital in Kirumba with my mother. My brother, Kambale Makembe, was 19 years old and in the hospital for appendicitis. As we walked, I saw them – people I knew weren’t from here. The word “refugee” wasn’t in my vocabulary at that time, but I knew these people were running from their homes, looking for peace.

The sadness on their faces was so visible that I sympathized with them. They carried mattresses on their heads and basic supplies on their backs. In my heart, I wondered why they didn’t enjoy the same things I enjoyed: protection, shelter and food.

Some of those refugees found shelter in churches and schools in our town. I vividly recall accompanying my mother as she took food to a group of them at a nearby church. I saw hungry and half-naked children crying. Their parents seemed confused, not knowing what to do.

Curious onlookers swarmed to watch these refugees. For many of us, it was the first time we were seeing people from other places.

Later that evening, I described the scene to my brothers and sisters.

“Listen,” my elder brother said. “These people are criminals who have been expelled from Rwanda. After killing their compatriots, they fled here. We aren’t immune from them and they can do us harm one day.”

With his words, I developed a pathological fear of Rwandan refugees. We were sure that they had killed many people in their home country, and that they would do the same here.

It was a cruel irony that not two years later, we became like refugees ourselves.

Chapter 4: History

First and Second Congo Wars

Beginning in 1993, the Wangilima and other armed groups known as Mai Mai killed thousands of people and displaced an estimated 300,000 people in DRC’s North Kivu province. This was part of a vast, coordinated effort to rid what was then Zaire of Rwandans and people with Rwandan ancestry, according to Human Rights Watch.

An additional 18,000 people were displaced from North Kivu province in 1996. The violence in the area sparked what is known as the First Congo War. Military forces from Rwanda and Uganda that backed Kabila pushed into eastern DRC on their way to Kinshasa, the capital city, where Kabila took control of the country in September of 1997.

Unrest in eastern DRC continued as Kabila’s loyalty shifted away from Rwanda and Uganda, sparking an invasion from those countries’ troops in 1998. That conflict, called the Second Congo War, ended in 2003.

Kabila was assassinated in 2001 and his son, Joseph Kabila, took power and kept it until January of this year. These abrupt and complex political maneuvers left eastern DRC in a state of constant flux, with unprecedented numbers of internally displaced people and refugees moving from one place to another.

The Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), a group made up primarily of members of the Rwandan government and army who were pushed out of Rwanda after the genocide in 1994, became active in the later stages of the Second Congo War and remain active today.

An estimated 5 million people died during the first and second Congo Wars, between 1996 and 2003.

After the Congo wars, eastern DRC has remained a hub of insecurity as more than 130 armed groups continue to actively battle each other, DRC’s military or U.N. forces. Reasons for the fighting vary, from control over resources to the illegal taxation of everything from minerals to goods to movement on certain roads.

Chapter 5: Recollection, 1996

“We hid in the valleys, beneath the banana leaves.”

The wave of violence that came to Lubero territory in 1996 was severe. We had been displaced by the AFDL that same year and returned to the tenuous peace we’d made with them, but the disruption to our lives continued.

Our resource-rich region was sought after by military factions and local armed groups, known as Mai Mai. All of them brought their own violence and their own rules.

Mai – or maji – means water in Swahili, a language spoken widely in North Kivu province. Mai Mai groups are believed to wash themselves with magic water that protects their bodies from bullets. It sounds fantastical, but we believe that, in some cases, these Mai Mai fighters do have supernatural protection. If you heard enough stories – eyewitness accounts from people you trust – of men who repel bullets or fail to bleed when knives pierce their chests, you’d begin to believe it too.

Mai Mai groups vary widely in their purposes and tactics. Some small groups are formed by as few as 20 men who want to protect their own villages. Other, larger groups can have as many as 200 members who seek to control key roads or entire regions. Some of the most notorious operate in Virunga National Park, a jewel of DRC known for its natural wealth and animals, including mountain gorillas. There, Mai Mai groups sometimes slaughter park rangers and animals in their quest to control land and make money.

When the Mai Mai came, some of our people were killed, some were wounded. Some disappeared and others lost their property.

We hid in the valleys, beneath the banana leaves. Our fear was great because rumors circulated that the military could see us with their binoculars. We didn’t know where to hide our heads.

Everyone in my town who experienced this remembers it keenly. For some, it was a continuation of the terror that happened when the AFDL came.

Kavira Shalikowiwe is my father’s cousin. I call her my aunty. Now 50 years old, she had three young children at the time. When the AFDL came, she grabbed her children and hid in a field her parents owned.

“We lived there for two months,” my aunty remembers.

And when the Mai Mai came, my family, too, hunkered down in the fields. We brought basic supplies from home, mostly beans and cassava or maize flour. We brought two cooking pots and a jerrycan that we used to fetch water from a nearby river. The men helped each other erect small shelters from trees and grass.

We dreaded the night because we lacked a secure place to sleep. When it rained, we huddled together, trying to stay warm and dry.

When our food ran out, we scavenged in our fields for cassava and potatoes. There was no meat, except when we caught forest rats.

That year, I was 17 years old and seven months pregnant. But I couldn’t get to a doctor for any checkups.

When we saw the Rwandan refugees, we never imagined it would be our turn so soon.

But unlike the refugees, my family never tried to leave our homes for good.

My father, Matayo Luneghe, is a short man who carries his family’s farming legacy with pride. He sometimes left us behind in the field to scout out what was going on in town. Over and over, he crept up to the edge of our own neighborhood and watched. He did that many times, over a period of months.

Even in that era, my dad was respected because he knew what was going on in the region and even beyond DRC’s borders. He listened to the radio and passed the information along to other people in Kirumba. Even today, a visitor to Kirumba can ask for him by name and local people will know who he is. He still works his land in Kirumba and his family’s land in Hutwe.

From 1996 on, the ability to negotiate with Mai Mai leaders became a prized skill. Stino Muhindo Sivyaghendera, now a neighborhood chief, was in his early 20s then. It was during this era that he honed his diplomatic techniques. He asked Mai Mai leaders about their expectations and how they would enforce their rules.

Once we accepted their rules, the violence stopped. But it would soon start over, and over, again.

It was an exhausting way to live.

I remember asking my dad why we had to live like this. Why couldn’t we leave to find stability elsewhere?

But leaving was an idea he wouldn’t tolerate.

To leave, he told me, would be to give our land to the enemy. It would be a betrayal of our culture.

He never imagined a scenario in which we would leave and never come back.

Anyone who wanted to help us should help us here, on our land, he told me. We shouldn’t have to go to a camp for someone to offer help.

In a camp, he said, we’d more likely die from hunger.

When the time came for me to have my first child, my dad negotiated with the Mai Mai to secure our safe return to our home. I delivered my daughter there.

Chapter 6: History

The Frantic Exoduses of Entire Communities

Tracking the numbers of internally displaced people, IDPs, in eastern DRC is difficult, in part because aid groups can’t reach many of the displaced communities. Travel throughout the region is difficult and dangerous. Mai Mai groups control portions of major roads and force travelers to pay bribes that they call taxes. In some cases, travelers are robbed or killed.

MONUSCO, the U.N.’s peacekeeping force in the region, operates an armed convoy that travels nearly 190 miles between Goma and Butembo, a town that hugs the western edge of Virunga National Park. GPJ reporters who are based in North Kivu and Ituri provinces, say the convoy is the safest way to move through the region, but tensions are high even when traveling with it.

When communities are trapped by a combination of dense jungle and marauding Mai Mai groups, it’s not possible for aid groups to reach them and provide assistance, says Chrispin Mvano, a Goma-based researcher who tracks armed group activity and the status of internally displaced people, or IDPs, here.

Like the situation in Kirumba in 1996, frantic exoduses of entire communities are still common in eastern DRC. Today, Kirumba is considered a beacon for people in villages throughout the area who say Mai Mai groups have made it too dangerous to remain at home. An estimated 5,000 people have moved to Kirumba in the past two years, leading to overcrowding and serious tensions.

Throughout North Kivu, it is estimated that about 80% of IDPs live with host families instead of in camps.

That’s often preferable to life in formal IDP camps, where conditions tend to be poor.

“People who are there have no access to food, no access to water – it’s like a cemetery,” Mvano says.

Even if IDPs hear that their home villages are no longer under Mai Mai control, they often can’t return, Mvano says. Members of the national army often occupy land that has been abandoned by people fleeing violence, he says, and the government has never been able to provide long-term security, making it likely that another armed group might soon move in and force local people to leave all over again.

Now, many IDPs have been away from home for so long, some for more than 15 years. But the formal data that tracks their numbers is misleading.

In 2018, the DRC government and the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) agreed to change the definition of IDPs here to exclude anyone displaced for more than one year. After this change, OCHA reported that there were 1.37 million IDPs in the country, a drastic reduction from the more than 4 million IDPs counted just one year before. The change in definition doesn’t reflect a change in the reality for displaced people here.

Chapter 7: Recollection, 2011

“Registering as a refugee is like signing up for college.”

Everyone knows someone who has lied to become a refugee. They tell the aid officials that they’re orphans or that they’re in imminent danger.

Harlette Kavira, who is not related to me, lives in Kirumba. In 2011, she says, her sister, then 27 years old, went to Goma to visit family. She never returned.

One day, a shopkeeper from Kirumba who was on one of his regular business trips to Uganda saw Kavira’s sister in Kampala, the capital city there. She was living in a refugee camp, awaiting resettlement.

“She had declared that she had lost all the members of her family,” Kavira says, explaining how her sister was able to get refugee status.

Five years later, her sister was sent to Australia under a refugee resettlement program. Australia only accepts refugees who prove that they would be in danger if they returned home, need specific medical treatment or don’t have any other place to go.

She became famous in Kirumba for her sly trick. And she’s not the only one.

Eventually, she contacted her family in Kirumba online.

“She apologized for the fact that she declared us dead,” Kavira says.

Of course, every town has its adventurers – those people who leave as soon as they’re old enough, because they have a taste for exploration or the dream of a better or different life. But that’s different than the people who become refugees by choice.

“Those who want to become refugees are lazy people who like an easy life,” says Zaidel Ngolo, president of a youth council in the South Lubero area.

I once saw a man on a bus who carried a sleeping mat with him. This was in 2012, during a period of calm when there wasn’t much local migration. I asked him why he was traveling and he told me he was going to register as a refugee at Mugunga Camp, a sprawling settlement for displaced people near Goma, the capital of DRC’s North Kivu province.

I asked him why he couldn’t stay in his village and work the land. He told me that he was ready to walk away from his agricultural inheritance for the chance to move to a high-income country. I was astonished to meet someone who would choose to become a refugee even while admitting that his home was safe.

In many cases, though not all, the people who are in actual need of urgent relocation are most often in isolated areas, blocked off on all sides by inhospitable geography or violent armed groups. If aid agencies were able to get to these places, the people there would also be able to get out and away from the danger.

It’s only when the violence subsides and the roads become safe for travel again that people can even get to the places where refugee services are available.

In DRC, for some people, registering as a refugee is like signing up for college. You’ll go live somewhere else, under the care of an organization that is tasked with feeding and housing you.

Cases of refugee fraud aren’t uncommon and are often caught by settlement agencies or even foreign governments.

In any case, the population of Congolese refugees is growing across the world.

Chapter 8: History

A Congolese Refugee Boom

The world is now home to more 70 million refugees and displaced people. New data suggests that some 37,000 more are forced to flee their homes every day.

Every country uses different criteria to identify and admit refugees, but the definition that matters most in central Africa is the one used by the United Nations, which has a hand in administering many of the region’s refugee camps. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “A refugee is someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war or violence.” The person must have a “well-founded fear of persecution for reasons of race, religion, nationality, political opinion or membership in a particular social group.”

“Most likely, they cannot return home or are afraid to do so,” the definition continues.

Though not formally declared, eastern DRC has been in a state of war, or at least consistent conflict, since 1996. That has caused a boom in Congolese refugees settling around the globe.

In 2018, North and South Kivu provinces had a violent death rate of 8.38 civilians per 100,000 – more than double the rate of Yemen.

In July 2019, UNHCR projected that Congolese refugees will have the third highest need for global resettlement in 2020, behind Syria and South Sudan.

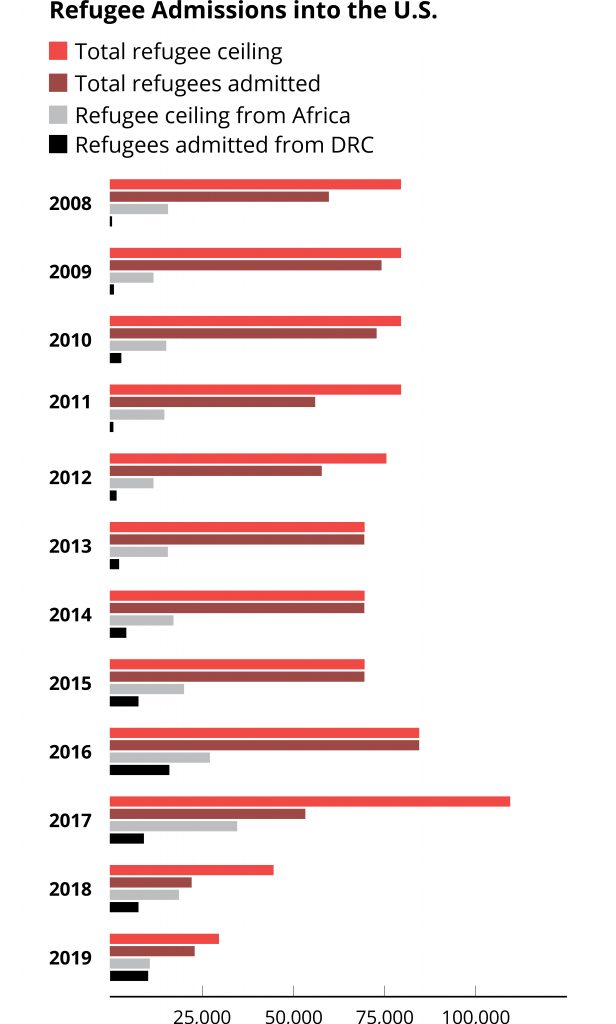

More than 765,000 Congolese refugees have resettled on the African continent as of September 2018. And more than 70,000 refugees from DRC have come to the U.S. since 2002, according to an online database maintained by the Refugee Processing Center, a division of the U.S. Department of State.

Just under 20,000 of them came in 2016, according to that database. In 2018, about 9,300 Congolese people arrived on U.S. soil. More than twice as many refugees were admitted to the U.S. from DRC than from any other country in fiscal year 2018, according to early 2019 data.

Congolese refugees are most often admitted into the U.S. for humanitarian reasons or to reunite with family members who had previously been granted refugee or asylum status. The family reunification criteria was scrapped in 2008 due to many allegations of fraud. But it was reinstated in 2012 with new requirements, which now include DNA evidence.

So far, the controversial decrease in the number of refugees allowed into the U.S., imposed by the Trump administration, has not hampered applications from people in DRC. The ceiling for all refugees from Africa this year is 11,000 and 10,377 of those spots have gone to people from DRC, as of October 1.

Still, deciding whether to stay or go is a complicated choice.

Chapter 9: Recollection, 2008

“We live in the air.”

When an armed group comes through town, we listen first. Then, we determine whether we can have a dialogue with its leaders. We send mediators – our own neighborhood representatives – to find out whether the group’s standards are tolerable.

Then, each person, each family makes a choice.

Those who feel that they can tolerate the group’s demands stay. Those who can’t head to the bush or to a temporary camp.

It’s a consistent pattern for us.

There is a saying in DRC that we use to convey the precariousness of life and our lost sense of home: “We live in the air.”

I remember when the Wangilima came back to Kirumba in 2008, there was another period of real terror. Their stated goal, protecting Congolese people from foreigners, hadn’t changed. They thought of themselves as “Balinda Amani” – protectors of peace in Swahili.

But they went about their mission with extraordinary violence.

More than 20 years after the Rwandan genocide, they were looking to kill anyone rumored to have Rwandan roots, even babies. And when they arrived in Kirumba, they started to kill people with machetes, even those who weren’t Rwandan but had been accused of a variety of crimes or actions.

Once, I saw with my own eyes, two girls hacked to death. The Wangilima had accused them of practicing witchcraft.

“They told us to tell people not to be afraid,” remembers Paluku Kingaha, a 62-year-old neighborhood leader.

But when the Wangilima clashed with the AFDL, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo, we ran to the forest to hide. Again.

When we wanted to return we were told that we needed to pay a tax to guarantee peace. Again.

Around that time, the Congolese government announced far and wide that members of the FDLR – Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda – were expected to surrender themselves and their weapons. The official goal was to demobilize them and deport them to Rwanda, but in reality, they were mercilessly hunted down.

I was 29 years old in November 2008. I had been married. I had two children of my own, and I was one of the lucky ones: Instead of living hand-to-mouth, I worked at a community radio station called Radio Communautaire Tayna in Kasugho, a village about 40 kilometers (25 miles) northwest of Kirumba, as the crow flies. My job was to send messages to the station’s branches in Goma to the south and Butembo to the north on behalf of the station’s chief.

The station aired announcements that encouraged FDLR fighters to surrender, but we paid a huge price for that. Soon, the FDLR turned its sights on the station. Bullets started whizzing around one night and we all fled for our lives. The station was burned to embers.

So, I returned to Kirumba, my hometown.

The FDLR soon dissolved into Virunga National Park, the treasure trove of endangered animals and valuable natural resources. And they are still there today. Looting, killings and destruction in the park continue regularly.

Epilougue

Kirumba, DRC, present day

So that’s where we are. Many things have changed. And many things have stayed the same.

You might be wondering, with all of this, why do I stay?

I know I have the option to leave.

I could move to Goma, where other GPJ reporters are based. But there are no other journalists working in Lubero territory. It is my duty and my honor to tell the stories of my place.

I stay because this is my home.

I was born here. I grew up here. My family is here. Recently, I built my own house here.

I have seen this place in times of peace and in times of war. Both ways, it’s my home.

In the course of my life, I have had to flee this place many times. But every time I have fled, I have done so with the knowledge that I will return.

I often recall my favorite line in a fable by Jean de La Fontaine: “Beware of selling the estate our fathers left us, purchased with their sweat. For there are hidden treasures there.”

And so, I will not leave this place. I will stay. I will stay for my family.

I will stay for you. I hope my journalism reminds you that there are real people here.

And most of all, I will stay for me. If I left, I know I would never have peace of mind. I love this place. It is my heart’s home.

Story, photos and audio by Merveille Kavira Luneghe, GPJ DRC

Additional reporting provided by Noella Nyirabihogo, GPJ

Drone footage by Alain Wandimoyi and Moise Musafiri Ntamuhanga, GPJ

Design and creative direction by Katie Myrick, GPJ

Research by Bennett Hanson, GPJ

Photo, video and audio editing by Austin Bachand, GPJ

Translation by Ndahayo Sylvestre, GPJ

Editing by Krista Kapralos, GPJ

Story coaching by Jacqui Banaszynski

Fact checking by Terry Aguayo, GPJ

Copy editing by Seher Vora, GPJ

Illustrations by Matt Haney for GPJ