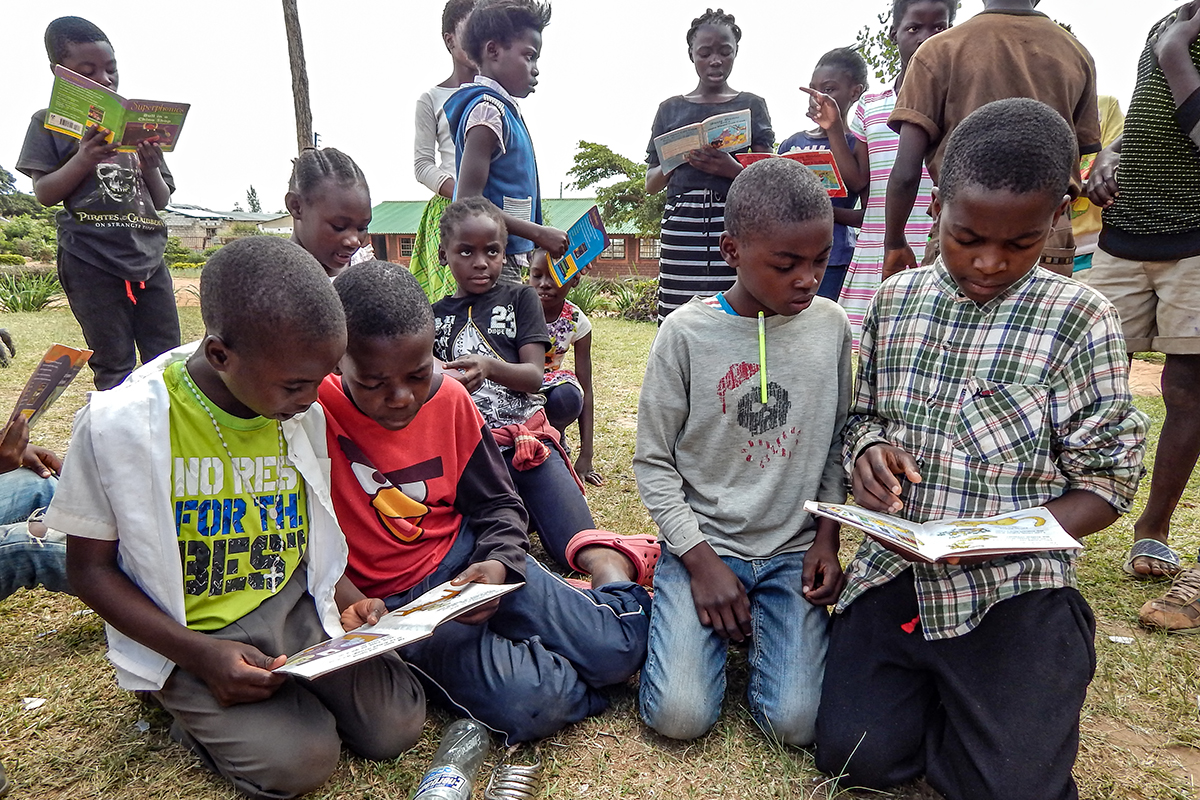

Prudence Phiri, GPJ Zambia

Children read story books during a break at Shine Zambia Reading Academy in Lusaka.

LUSAKA, ZAMBIA – In a small classroom, students take turns scribbling vowels on a blackboard while sounding out the letters.

“We teach the pupils in a local language, for them to easily grasp the concept,” says David Mulenga, referring to reading. The head teacher at Shine Zambia Reading Academy in Lusaka, Zambia’s capital, teaches his students to read and write in Nyanja, a local language, as well as in English, the country’s official language.

This method of teaching is growing in some parts of the country but declining in others, Mulenga says over the students’ chorus.

Zambia’s low literacy levels prompted the government to significantly broaden the use of local languages in primary schools five years ago, making English secondary in teachers’ communication with their students. The shift has improved reading and writing among the students who now receive instruction in the same language they speak at home, advocates say. But others argue that the policy has created even more challenges.

The quality of education in Zambia is low, despite many positive developments, such as improved access to education and rising enrollment rates. Literacy levels are one of the education sector’s greatest problems, experts say. An estimated 35 percent of Zambians ages 15 to 24 are illiterate, the highest rate in southern Africa, according to Creative Associates International, a global development organization.

In 2013, the government took broad steps to reverse low literacy levels with its National Literacy Framework, a policy that promotes instruction in local languages. Students in grades one to four — those between the ages of 7 and 13 — are to be taught in their local languages instead of in English. Zambia has more than 45 languages.

A year after the policy was implemented, there were still challenges. Students in grade two who received instruction in their local dialect fared better on a 2014 assessment, but they still struggled. In most cases, more than half of the children could not read passages in the predominant language of the area where they attended school, according to a 2015 assessment survey. At worst, on the Chitonga-language test, 88 percent of students could not read any words correctly.

Henry Tukombe, permanent secretary for the Ministry of General Education, says Zambia’s Education for All 2015 National Review, however, shows that overall literacy and numeracy rates in the country have improved. Teacher-student interactions are contributing to the improvements, he says.

There is more frequent communication between students and teachers, who are now more comfortable using local languages in instruction, Tukombe explains.

Joshua Lungu, a 9-year-old student at Shine Zambia Reading Academy, says learning how to read in his local language has improved his academic performance.

“When I started school, I could not understand English,” he says. “But because the teacher taught us in Nyanja, it became easy to understand.”

But for some, local languages get in the way of academic progress.

Peter Bwalya comes from Kalomo in Zambia’s Southern Province, but he attends Mtendere Primary School in Lusaka. Because he grew up speaking Tonga, it is difficult for him to learn in Nyanja, a local language spoken in the capital and surrounding areas.

But Tukombe says many young students have the ability to learn quickly.

“Children easily learn, so that is not a problem,” he says. “The only challenge we are having is equipping all teachers with all the local languages, just in case of a transfer to a different province.”

While public schools are sticking to instruction in local languages, some private schools are using techniques similar to Mulenga’s.

“Although the law is for all, private schools that feel they can’t enact it are not mandated to,” Tukombe says. “There are no penalties for not following the law.”

When the policy was introduced, some parents didn’t want their children to be taught in local languages, because they thought it would limit the children, says Gloria Kafusha, owner of Munso School, a private school.

Mulenga says that the solution to improving literacy is not the use of only local languages in communication for all four grades of primary school.

“As much as it is helping the children to easily comprehend and grasp the concept of learning, teaching them in a local language for four years is detrimental to their development,” he says. “Once you change the language of instruction to strictly English, it becomes a struggle for them to adapt.”

Mulenga says he teaches his students in English as soon as they start to read.

Prudence Phiri, GPJ, translated some interviews from Nyanja.