anori Wijesekera, GPJ Sri Lanka

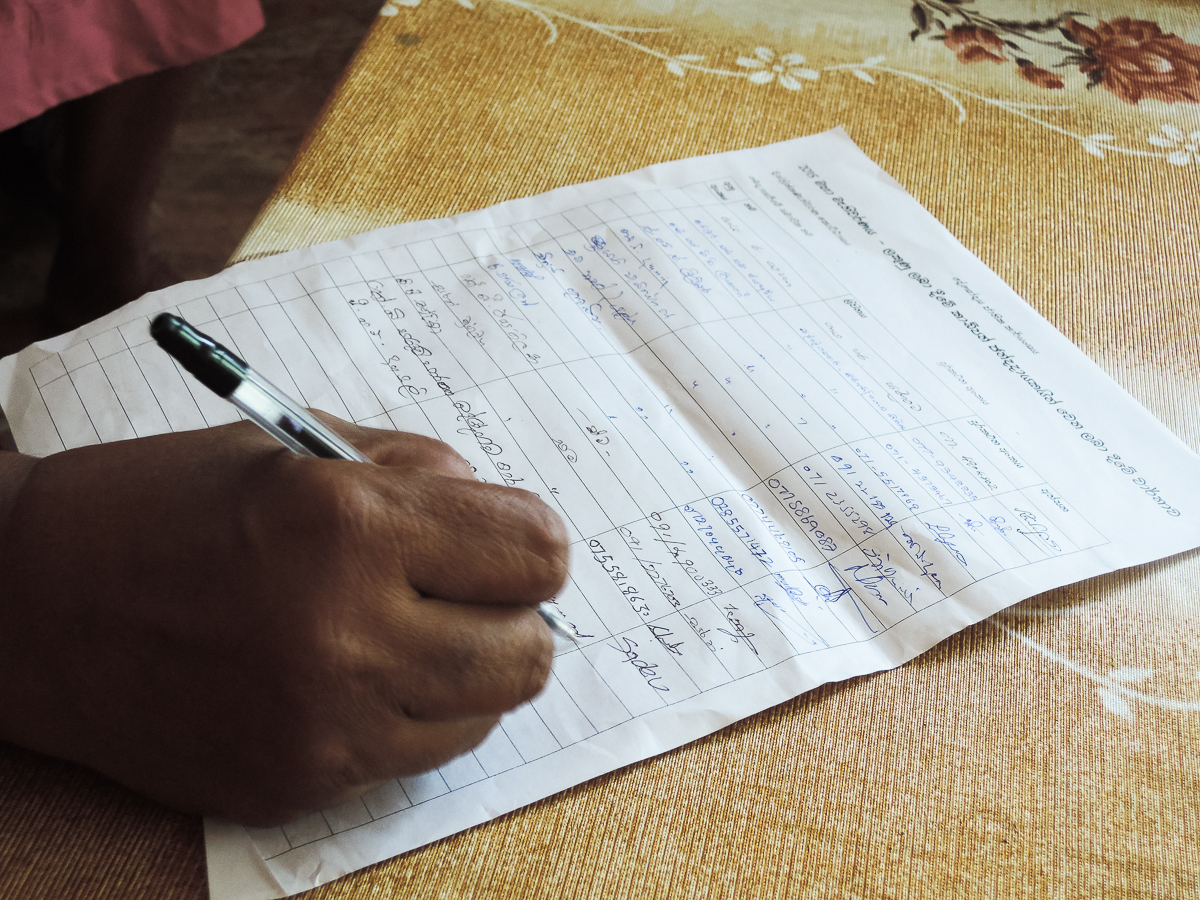

A.G. Ranjini (left) and Greeta Dias Nagahawatte (right) explain the details of the March 12 scorecard to G.M. Dayaseeli in her home.

COLOMBO, SRI LANKA — Luwie Ganeshathasan, 28, remembers the first time he saw corruption in full view. At 13, he accompanied a family friend who needed to clear a foreign parcel from Sri Lanka’s customs office. The friend had to bribe almost every official they dealt with. Ganeshathasan says he watched, dumbfounded.

“I never knew until then how ingrained corruption was,” Ganeshathasan says.

Ganeshathasan’s experience is normal in the country, where many political and police activities involve corruption, residents say.

Anti-Corruption Advocates Take Message Nationwide

But on Aug. 17, when voters head to the polls to elect a new Parliament, that could all change. For the first time in Sri Lanka’s political history, all of the 17 major political parties have signed a pledge to exclude candidates who have served jail sentences, been proven guilty of bribery or corruption, engaged in the illegal sale of alcohol or drugs, operated casinos or prostitution networks, or participated in other questionable activities. The pledge, which asks the political parties to commit to eight values, was created on March 12 by a dozen organizations led by the People’s Action for Free and Fair Elections, or PAFFREL. Those organizations are together known as the March 12 Movement.

“For the first time, politicians are beginning to understand that corruption is something that can cost them an election,” says Ganeshathasan, who is not connected to the March 12 Movement.

The demand for clean politics has been building in recent months among Sri Lankans who are fed up with a system that has been increasingly greased with off-the-books deals between politicians and moneyed criminals.

Corruption became more widespread under the autocratic government that prevailed in Sri Lanka for the past decade, says Jayadeva Uyangoda, political science professor at the University of Colombo.

That corruption, and the opaque government that makes it possible, has deeply penetrated Sri Lankan life. And investigating government actions is dangerous – sometimes lethal. Sixteen journalists were confirmed killed in Sri Lanka between 2004 and 2014, according to the Committee to Protect Journalists, an independent nonprofit organization that promotes press freedom.

President Maithripala Sirisena leveraged the country’s frustration when he campaigned for office before the January 2015 election. Sirisena campaigned on a platform of reform and legislative change that he said would introduce a transparent and corruption-free government. He won the closely contested January election with 51.3 percent of the vote. The Department of Elections recorded a voter turnout of 81.5 percent of registered voters – the highest recorded voter turnout for any presidential election in Sri Lankan history.

“Some people call the January election ‘the Rainbow Revolution’ because it opened up the political change and better democratic governance,” Uyangoda says.

But before introducing all the planned reforms, Sirisena dissolved Parliament on June 26 and fixed new parliamentary elections for Aug. 17, hopeful that a fresh group of lawmakers would be more inclined to approve his proposed reforms. Members of Parliament, representing 22 electoral districts, are elected to 196 seats in a proportional representation system.

“Although political parties have been talking about nominating the right candidates during past elections, it is only in the August elections that the qualifications of the candidate and his or her ability have come to the forefront,” Uyangoda says.

A total of 21 political parties and 201 independent groups are fielding 6,151 candidates in the August elections, according to the Department of Elections.

This is the first time eligibility criteria for political candidates were presented in public, says Rohana Hettiarachchie, executive director of PAFFREL and spokesperson of the March 12 Movement.

“This had become a societal need,” he says. “We distilled a widely felt public concern, documented it, and arrived at a consensus to initiate a debate in society. Now everyone is taking it forward.”

Over the course of 2013 and 2014, PAFFREL gathered more than 100 recommendations for eligibility criteria from business and social groups, then extracted eight core criteria: The candidate should not be a criminal, should not engage in bribery or corruption, anti-social trades, environmental pollution, or abusive financial contracts, and should not abuse authority. The pledge also states that candidates should be close to Sri Lankan voters, and should provide adequate political opportunities for women and youth.

Hettiarachchie believes the March 12 Movement can influence 30 to 40 percent of voters at the August election.

All the main political parties in Sri Lanka signed the March 12 Declaration – the pledge to adhere to those eight core values when selecting parliamentary candidates, but many failed to live up to their word, Uyangoda says.

“The irony is that the very party secretaries and leaders who signed the pledge have also signed nomination lists that are alleged to include people with criminal records and allegations of corruption,” he says.

Hettiarachchie says he expects parties to go back on their pledge.

“We know very well that those who signed will not follow up on it,” he says. “So when we discussed what to do about it, we agreed on the need to form a movement to campaign for it.”

The March 12 Movement and PAFFREL have not scrutinised the backgrounds of the 6,151 candidates seeking election to Parliament from all electoral districts, so they cannot say with certainty which candidates do not comply with the eight core values.

It’s not easy to change a political culture that has lasted for 20 to 25 years, Hettiarachchie says. But change is happening, he says, citing one prominent political party that did not nominate four of its senior members because they had served prison sentences or were under police investigation.

“We are not claiming that this was because of the March 12 Movement, but definitely the concept of eligibility criteria is now in the public discourse,” Hettiarachchie says.

Ilankai Thamil Arasu Katchi, ITAK, a constituent party of the Tamil National Alliance, the governing party in the Northern Provincial Council, signed the March 12 pledge.

“The March 12 Declaration was a conscience-raising attempt to the voting public and also to the political parties of their role in giving nominations, to be mindful of these particular things,” says M.A. Sumanthiran, the deputy general secretary and the spokesperson of ITAK.

Cleaning up Sri Lanka’s political system might take more than electing honest parliamentarians. Uyangoda believes a new government, even one made up of clean politicians, will find it extremely difficult to reverse practices that have been common in Sri Lanka’s politics and economy for years.

“But the fact that there is pressure from society, pressure from activist groups, is very important because it will act as a societal check on the government,” Uyangoda says.

Previous governments indulged in corrupt practices with a sense of impunity, he says. But that is no longer possible. Politicians have received the message that there is no longer such impunity, he says.

The Sri Lankan public and media now openly discuss past abuse of power and allegations of corruption against individual politicians, Uyangoda says. There are social media campaigns demanding change. That public discourse is happening in a loose, organic way that shows that citizens want to hold their new government accountable.

“They may not be able to prevent corruption or eradicate it, but at least they can minimize it,” he says.

The change will be gradual, says Karunasena Kodituwakku, a senior member of the United National Party, the main ruling party, which signed the March 12 pledge. The party held workshops for its candidates to make them aware about the Code of Conduct issued by the commissioner of elections, Kodituwakku says. At these gatherings, party leaders laid out the values of the party and ensured that everyone understood what was expected from them.

Although the party has always held workshops for candidates, this year it made them mandatory, he says.

“We are serious about the values of good governance,” he says.

Some voters are skeptical that the movement will produce long-term change.

Neil Abeysekera, 78, a consultant civil engineer, says he is disappointed that some political parties have not followed the March 12 Movement’s candidate criteria.

“I think it’s because some parties have got used to greed, and can’t let go of corruption,” he says.

Others are hopeful.

Chethika Hapugalle, 43, the general manager of a paper products company, says she believes it is possible to clean up Sri Lankan politics.

“The introduction of eligibility criteria for candidates is promising – it’s a step in the right direction,” Hapugalle says.

The January election changed the country’s political course, she says.

“It was the first time in a number of years when the people decided for themselves, and elected to change the way things were,” she says. “It was a victory for the people.”

Manori Wijesekera, GPJ, translated two interviews from Sinhala.