SONIPAT, HARYANA — Saroj Narwal gets emotional when she remembers her farming days.

It was tough work. After finishing household chores in the morning, she would spend the whole day on her land, tending to crops along with her five sons. She says there were always tasks she could never quite get around to.

But today, things are different. “There is nothing much to do now,” she says, as she caresses and feeds a buffalo by the shed where it sleeps.

Narwal’s family owns nine acres of land in Kathura village, located in the northern Indian state of Haryana. They used to rent an additional 40 acres from other farmers to grow wheat, rice, sugarcane and other crops. But three years ago, they had to stop renting the extra land and switch to dairy production. The returns on their crops had become too poor.

The family still uses a small amount of land to grow sugarcane, without substantial results. With higher labor costs and lower market prices, the profit they make from the crop has dropped from 2,000 Indian rupees ($29) per acre each year to 1,000 rupees ($14.50).

The majority of the farm is now given over to livestock. Narwal’s family owns 27 buffalo, which earn them a monthly profit of 50,000 Indian rupees ($723). Most of that goes towards paying off a loan of 2.2 million rupees ($31,830) that they took out from the Punjab National Bank to buy the herd, she says.

Narwal is one of the millions of farmers in India who are struggling to make ends meet, and whose children won’t take on the traditional family business. A recent study by the Centre for Study of Developing Societies, a research center based in India’s capital, New Delhi, found that 67% of women working in agriculture felt that their family did not make enough money to feed everyone. The study also found that 76% of youth involved in farming did not want to continue their parents’ profession. (The age range for youth was not specified.)

Abhimanyu Kohar, a spokesman for Rashtriya Kisan Mahasangh, a federation of 180 non-political farmer organizations throughout the country, says market prices for grains and crops are not fair to farmers, given the amount they have to invest in their farms. He says most farmers in the state are making a loss at the moment, and not all of those families can afford to change their occupation like the Narwals.

“Everybody doesn’t have the luxury to change the livelihood means,” he says. “The farmer crisis won’t be solved until there are farmer-friendly policies.”

Roughly 35,000 farmers from around the country marched to New Delhi on November 30, 2018, to protest and demand a one-time unconditional loan waiver, increased subsidies and a special session in Parliament. The protest, one of several that year, came after a drought that began in late 2018 and has since grown worse, affecting more than 100 million people in India, according to the E.U.-funded Global Drought Observatory.

This agrarian crisis has led to a resurgence of farmers’ political influence. In an effort to double farmers’ income by 2022, the government raised the fixed prices of major export crops to be 50% higher than the production cost in 2018.

In December 2018, Prime Minister Narendra Modi introduced a scheme called Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi, designed to help struggling farmers. The scheme provides those who own less than five acres of land with 6,000 rupees per year ($88) in income support.

Still, farmers say their demands have not been met. Those who own more than five acres say they’re struggling too, with little prospect of help from the government.

Overall, Narwal and her family are doing better than when they had to stop farming crops, she says, but not as well as they used to do when the market for crops was good.

“Farming is our identity,” Narwal says. “We don’t want to leave it. Every time I think about our past farming life, it hurts.”

Saroj Narwal’s son, Akshay Narwal, 22, collects food for his 27 buffalo and transports it from the fields via donkey cart. He is one of five brothers who own nine acres of land in Kathura village along with their mother.

He says his family switched to dairy farming when they were struggling to make money growing crops. They’re still owed money from that time.

“We suffered huge losses in sugarcane and we have not even got full payment from the mills,” he says.

Akshay Narwal says he’s happier with the results from raising buffalo, but they only just make enough money to get by, with nothing left to save or invest for the growing family. Though rural incomes all throughout India have increased since 2008, they still remain far lower than the national average. A typical farmer in 2013 would earn 77,112 Indian rupees a year ($1,118), or 62% of the current national average income.

Saroj Narwal, 50 (right), stands with her sister-in-law, Anand Bhabhi, while carrying her 3-year-old grandson. The family started rearing buffalo and exporting the milk to New Delhi when their crop-growing endeavors failed three years ago.

“I miss my days in the farm,” she says. “We would spend our evenings and mornings in the field. But now they are just memories.”

In 1991, 63% of Indian workers were employed in agriculture, according to data from the International Labour Organization. But by 2018, that number had fallen to 44%.

A baby buffalo takes a curious look at the camera in the Narwal family’s livestock sheds. Saroj Narwal says she is responsible for supervising the animals to make sure they are in good health.

“These buffalo have their own language,” she says. “I always try to keep a check on them to see if anything bothers them – that they are taking their feed properly and giving milk.”

Budh Singh works in his wheat field in the village of Chinnoli in Haryana state. He grows different seasonal crops throughout the year across his land.

Singh says he took out a loan of 150,000 rupees ($2,170) in 2005 to meet his farming expenses. He has only been able to pay back 90,000 rupees ($1,302) of that in interest and says the main amount is still pending.

As politicians jockeyed for support from farmers during India’s elections in May, the alarming trend of suicides among farmers was often raised. More than 300,000 farmers in India have committed suicide between 1995 and 2015, according to data from India’s National Crime Records Bureau. Evidence shows that debt may be a factor; in 2015, the National Crime Records Bureau found that 82% of the 3,000 cases examined were farmers who had unpaid loans from local banks.

Budh Singh keeps most of his tools in a rusty closet next to his animal shed. He says he does not need them much these days, as none of his family participates in farming the way he did as a child.

Singh has three children, Navdeep, 17, Krishan, 19, and Jyoti, 22, all of whom are studying. They are not interested in farming, and Singh says he wouldn’t want them to be. His farm is currently running at a loss. He spent around 35,000 rupees ($506) on growing wheat last year and only made 32,000 rupees ($463). Singh says this is because market prices for wheat are low, and farm labor is expensive.

“I would never allow my children to do farming,” he says. “It would be like pushing them to starvation. Why would a parent want to do that?”

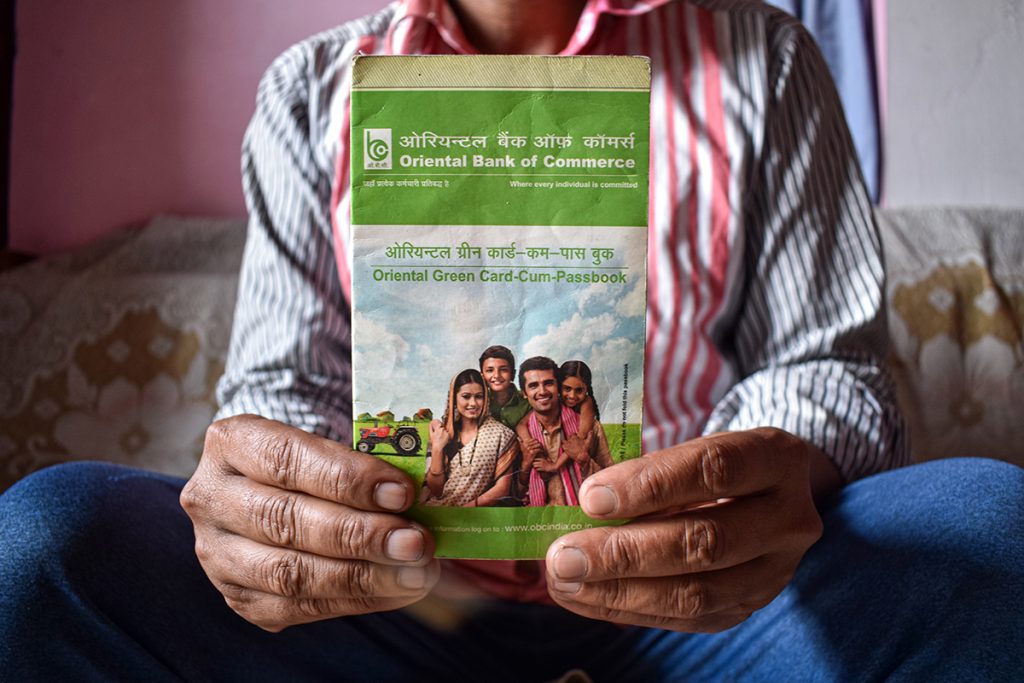

Dharm Raj Kohar, 43, displays a pamphlet for the Kisan Credit Card, another scheme introduced by the central government to help farmers. Under the scheme, Kohar has taken a bank loan of 300,000 rupees ($4,341) for the construction of his house, which he has yet to repay.

Kohar owns 2.5 acres of land in Chinnoli village. He rents another 2.5 acres from his brother, for which he has to pay him 15,000 rupees ($217) a year.

“Last year, I spent 40,000 rupees ($579) growing wheat and sorghum, including labor charges,” he says. “The return was only 37,000 rupees ($535).”

“Every year, I have to pay to the bank interest of 21,000 rupees ($304) and still I am not able to clear the loan,” he says.

Dharm Raj Kohar’s daughter, Bhawana, 19, is studying for a Bachelor of Arts by correspondence at the Indira Gandhi National Open University. She recently took on private coaching to help her prepare for the selection exams for posts in the Indian public service. Her father had to pay 10,000 rupees ($145) in advance for the coach.

“I know how difficult it is for my father to run the family,” she says. “I am working hard to make him proud and hoping I can get a good government job to help my father.”

On top of his farming work, Dharm Raj Kohar has a job as a security guard, earning a monthly salary of 7,700 rupees ($111). He says he would have never been able to pay for his children’s educational needs without it.

Kohar’s son Gaurav, 18, recently sat his final exams at school. Kohar says he wants Gaurav to get a job too, rather than taking on work at the farm.

“I will not even suggest to my enemy to do farming,” he says. “It wouldn’t be anything less than a curse.”

Tek Ram, 47, managed to turn his fortunes around by switching to organic farming. He decided to make the change in 2015, following several losses from his farm in the village of Sisana, located in India’s northern Haryana state.

“I started experimenting with my crops and using cow urine instead of market fertilizers and manure,” he says.

He says the organic crops he grows are worth more on the market and cost less to cultivate.

“On one acre of land, I cultivated 3½ kilos of wheat and the expenditure was around 20,000 rupees ($289),” he says. The full market value of the crops at sale was 60,000 rupees ($868), he says.

Aliya Bashir, GPJ, translated interviews from Hindi.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to clarify details about an academic study noting the interest of young people in farming.