Avigaí Silva, GPJ Mexico

Elena Izoteco and her daughter listen to Mass in an outdoor area reserved for the family and friends of patients at Hospital General Raymundo Abarca Alarcón in Chilpancingo de los Bravo, Mexico.

CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO, MEXICO — One long, cold, exhausting day last year, Elena Izoteco scrambled to get her pregnant daughter to a hospital. The family lives in Pochahuizco, an indigenous community tucked in the mountains of the southern Mexican state of Guerrero. During prenatal exams, Izoteco’s daughter had learned her baby was breech, or positioned to exit the birth canal feet first. Then, two weeks before her due date, her blood pressure spiked. She needed a cesarean section — immediately.

At the closest public hospital, staff told Izoteco’s daughter that no doctors could perform a C-section, a routine surgery to deliver a baby through the abdomen. So the family set off on an odyssey that’s become common for poor, rural Mexicans: They went to three different facilities, each farther away than the one before, until they found a hospital 36 kilometers (22 miles) from home that could help. That was not the end of their journey.

In Mexico, a public hospital stay is often a test of endurance for a patient’s family. They must stick by their relative’s side to advocate for their treatment, and sometimes to pay for bandages and medicine out of their own pockets — even if that means missing work and taking out loans to cover their bills. There’s rarely anywhere to sleep, so they camp outside the hospital, sometimes for weeks, usually with little shelter from wind and rain and limited access to food and showers.

By the time Izoteco arrived in Chilpancingo de los Bravo, the state capital, the sky was dark and the air brisk. Her daughter checked into Hospital General Raymundo Abarca Alarcón, which mostly treats patients without social security. Back home, Izoteco works intermittently planting corn. She doesn’t make much money, certainly not enough for a hotel room. She brought a backpack, the few Mexican pesos she’d scraped together and her other daughter, who came along because Izoteco, 50, does not know how to read. They spent the night on a bench outside the hospital, shivering under a thin blanket.

Drive by just about any public hospital in Guerrero, and you’ll see a similar throng of patient relatives and friends, the result of a strained health care system. In 2021, Mexico’s spending on public health was less than 3% of its gross domestic product. The country doesn’t have enough medical facilities, and the facilities it does have often lack equipment and staff, according to a report published by the University of California, San Francisco, in the United States. Mexico also has fewer doctors, nurses and beds per 1,000 residents compared to peer nations; in the poorest states, health care is particularly scarce. And between 2018 and 2020, residents of Guerrero, Oaxaca and Chiapas experienced the greatest decreases in access to doctors, medicines and dignified care in the country, according to Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, a national council that assesses social programs.

In a recent study, researchers interviewed patients and workers at public hospitals in a corner of Chiapas, the southernmost Mexican state, with few paved roads, little phone or internet service, and low literacy rates. In their telling, hospitals were imposing, dehumanizing institutions where doctors often refused to perform surgeries, sometimes because they lacked equipment or personnel, such as an anesthesiologist, according to the study, which was published in the medical journal The Lancet Regional Health — Americas. Health care workers often directed patients to other facilities, but that was no guarantee of treatment — they could easily face the same barriers at the next hospital, and the next.

One thing that helped: an advocate. A family member, or even better, an influential community member. The advocate lobbies on the patient’s behalf for medical attention, but they also purchase supplies for the doctor if, as is frequently the case, the hospital lacks antibiotics, syringes, bandages, diapers or sanitary towels. “This is the main reason why the patient is asked to come accompanied, because he is going to need something, and someone has to go and buy it,” says Dr. Maribel Guerrero Comonfort, a community physician who has worked in rural Guerrero. Better-resourced private hospitals usually have supplies on hand, but families like the Izotecos can’t afford to go there. (Representatives from both the state and federal health ministries did not respond to requests for comment.)

One day at the Chilpancingo hospital, a hostel at the facility for patient relatives was closed. Instead, the hospital directed families to a metal overhang outdoors that shielded benches; shelves for bags; outlets for phones; a vending machine with cookies and drinks; and a water cooler but no cups. Private vendors offered services, but the cost — 10 pesos (50 cents) to use a bathroom, 30 pesos ($1.50) to take a shower — was more than most families could pay. Midnight approached. People bundled in sweaters and jackets unfolded cardboard boxes to sleep on, or pulled blankets from their handbags to shield them from the stormy weather. (The hospital director did not respond to calls seeking comment.)

Natalio García Calleja ended up there when his pregnant daughter went into labor early; their local medical center didn’t have the necessary equipment to deliver the baby. The closest facility with an opening was the Chilpancingo hospital — 182 kilometers (113 miles) from their hometown of Pascala del Oro, a small Mixtec community. “It rained very hard. We had to wait until the rain passed to be able to rest a little, but we couldn’t sleep. You can’t sleep here,” he says. His wife was with him. “We covered ourselves with a sheet because we came unprepared. We didn’t bring anything, just a sheet.”

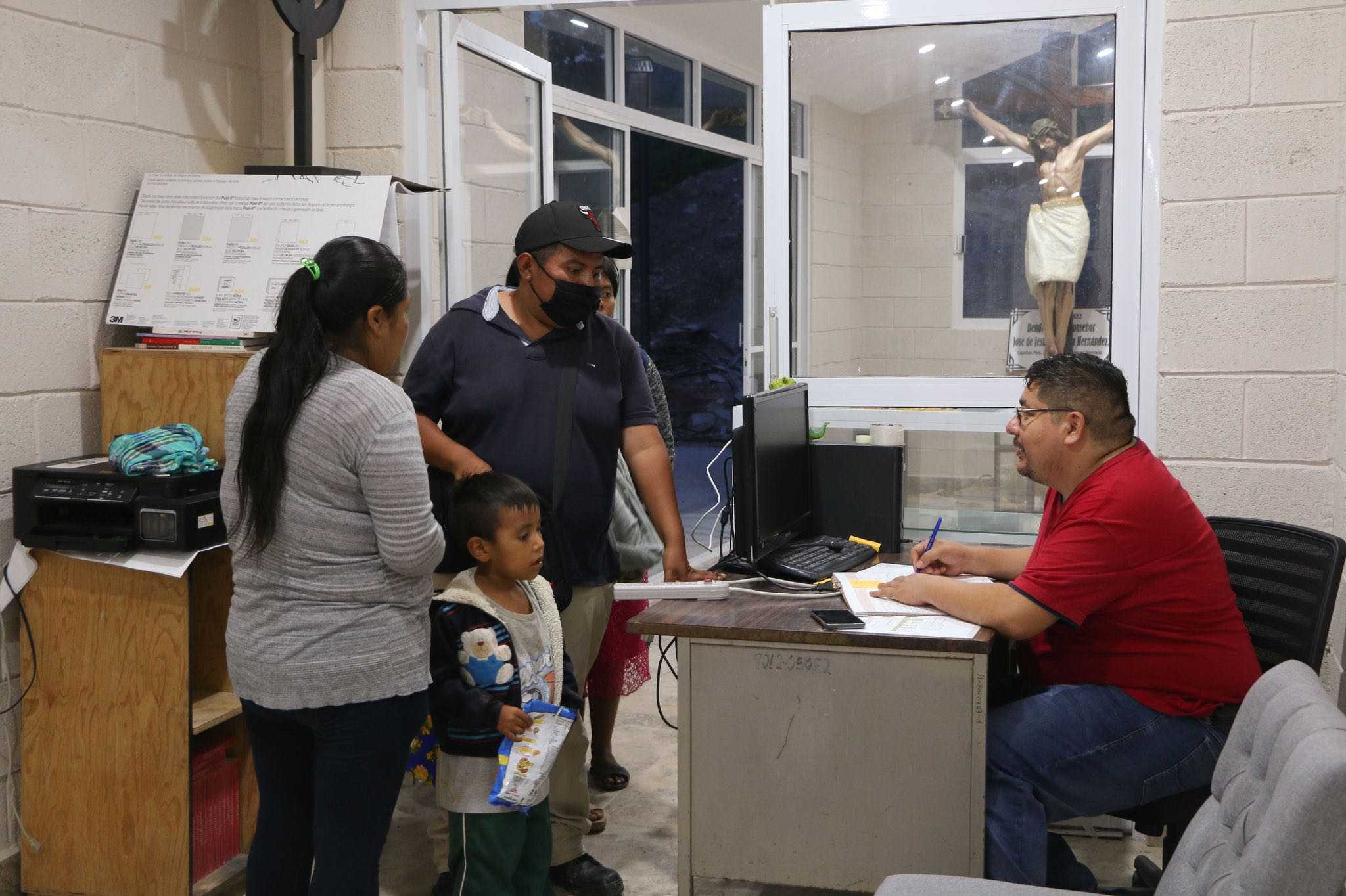

The next day, García heard about another option. In a sign of how entrenched the hospital encampment is, the local Catholic diocese recently opened a hostel for patient families called Capellanía de la Casa del Peregrino de Nuestro Señor de la Salud. Every Sunday, the Rev. José Filiberto Velázquez Florencio visits the encampment to say Mass and encourage people to partake of the hostel’s free food, toilets and showers. “It’s like an oasis in the middle of so many expenses and inconveniences that people have to deal with at the hospital,” he says.

Velázquez acknowledges the hostel is only a bandage for an ailing system, but for patient families, who arrive with so little, it’s a blessing. At the small, still-under-construction building, there’s room for maybe two dozen people to sleep; others drop by to shower, or to eat tacos or stewed eggs with tomato, onion and green chilies. Velázquez usually offers to visit their bedridden relatives or say a special Mass for them. García and his wife showered and slept there before heading back to the hospital to give their son-in-law a break.

For three days, Izoteco survived mostly by eating tacos that volunteers bring to hospital families and walking to the diocesan hostel to shower. Her daughter gave birth to a boy who was generally healthy but needed a minor surgery. Mother and newborn stayed at the hospital a little longer, but Izoteco couldn’t afford to — it was planting season in Pochahuizco, and she needed to get back to work.

Avigaí Silva is a Global Press Journal reporter based in the Mexican state of Guerrero.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Shannon Kirby, GPJ, translated this article from Spanish.