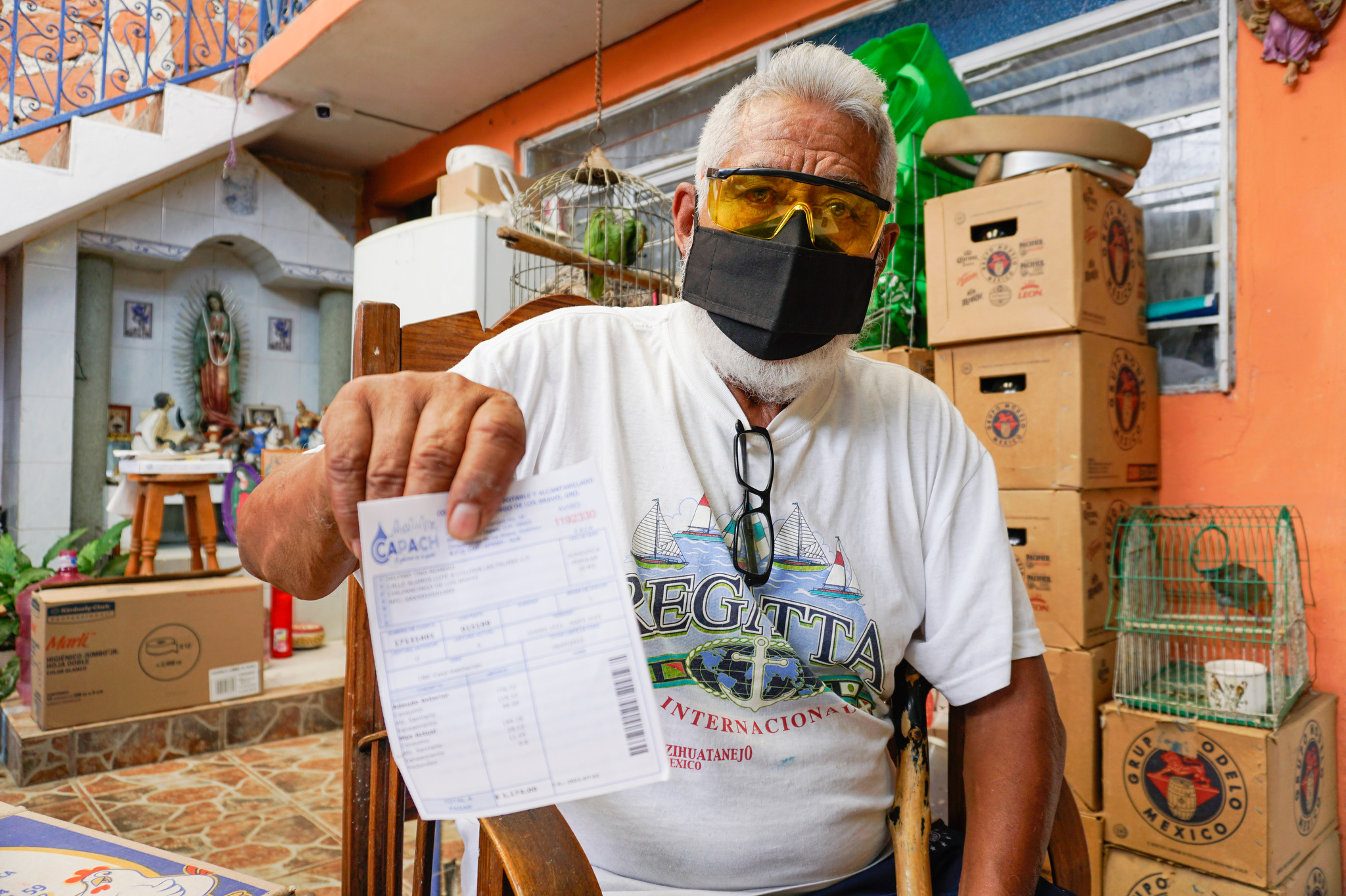

AVIGAÍ SILVA, GPJ MEXICO

Jesús Villafaña Marcos installed a rainwater catchment system to supplement the water his family must buy from private tankers.

CHILPANCINGO DE LOS BRAVO, MEXICO — Jesús Villafaña Marcos holds up the rainwater catchment system he installed using a piece of galvanized steel, a traffic cone, the disc of a TV antenna, and a plastic bottle.

“A rich man’s trash is a poor man’s treasure,” he says.

Handmade rainwater catchment systems hang from many homes in this area on the outskirts of Chilpancingo de los Bravo, a city at the foot of the Chilpancingo mountains in the southwestern state of Guerrero. They are, as Villafaña describes, “treasure” for his and other households in the Nueva Esperanza neighborhood.

But their role is changing amid increasing droughts, untamed urban development and inconsistent government services. In cities like Chilpancingo, rainwater catchments are used to ensure that households have access to a steady water supply.

When they don’t use rainwater they collect themselves, Nueva Esperanza residents must buy water from privately owned tankers — a significant expense for many families in a state where close to 70% of the population lives below the federal poverty line, according to a 2018 report from the government’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy.

Rainwater catchment systems are far from new; for more than 5,000 years, households and communities have collected rainwater for everything from domestic needs to watering crops. An estimated 100 million people around the world, mostly in rural areas, depend partially or totally on these systems.

Potable water shortages in Chilpancingo have gotten worse over the past 10 years, says Uriel Winston Cabrera Tena, a biologist and environmentalist. According to the National Water Commission’s 2018 report, “Statistics on Water in Mexico,” Guerrero’s annual rainfall in 2017 was less than the average annual rainfall in the years from 1981 to 2010.

The water shortages aren’t just a result of natural causes, though, Cabrera says, adding that deforestation and illegal logging contribute to the devastation of areas near the three groundwater reserves that serve Chilpancingo. That’s coupled with the city’s inconsistent water service. Many households have turned to rainwater catchment systems and private water tankers to mitigate an unreliable and, at times, nonexistent water supply.

Teodomiro Lara González is a retired captain in the Mexican army who lives in Las Palmas, another neighborhood in Chilpancingo. He says he hasn’t received water service for months, despite paying the bill, and he isn’t the only one. In the past several years, Chilpancingo residents have blocked the streets and organized protests to demand water service and call attention to shortages. They cite the fact that, in 2012, Mexico declared water a constitutional right for its citizens.

One cause of irregular water service is a debt of more than 70 million Mexican pesos ($3.5 million) owed to the Federal Electricity Commission, which provides the energy needed to distribute water, says Carlos Balbuena Schiaffini, director of the Potable Water and Sewage Commission of Chilpancingo at the time of the interview. The commission is the government agency responsible for the management of the city’s water supply. In December 2021, the municipal government paid 5 million pesos ($249,000) of that debt in an effort to improve service. Inconsistent water service is also in part due to overextension of services to newer neighborhoods as the city has grown, Balbuena says.

Regardless of whether residents receive water service, Balbuena says, charging the monthly quota of 90 pesos ($4.48) is in accordance with the Law of National Water — the law in Mexico’s Constitution that regulates the use, distribution and preservation of water — since the quota allows for the maintenance of the water distribution system.

The local government has offered some neighborhoods free water from tanks. But Humberto Sánchez Calvo, president of the development committee in Chilpancingo’s Bella Vista neighborhood, says this often isn’t enough.

To mitigate the high cost of buying from private water tankers, Lara has used a rainwater catchment system for 30 years, adapting a design he saw in other states during his time in the army. “Even though the drought this year was especially cruel, we didn’t have to buy water from tankers,” Lara says, referring to the dry season of 2021.

Other families are not as lucky. They may have catchment systems but lack cisterns or tanks to store the rainwater.

During the dry season, Maricela de la Cruz, a Nueva Esperanza resident, buys water from private tankers, which costs between 120 and 140 pesos ($6 and $7) for 1,200 liters of water. That is a considerable expense for de la Cruz, whose monthly income from her small grocery store and occasional family support is 3,000 pesos ($149).

“We reuse the water for washing clothes in the bathroom, and the water for dishes is then used to rinse off the street since there’s so much dust,” she says.

Balbuena says the most important way to address water shortages is for people to follow de la Cruz’s lead and reuse water whenever possible.

Roel Ayala Mata, the meteorologist and director of monitoring and risk analysis with Guerrero’s Ministry of Civil Protection, says that rainwater catchment systems can be a sustainable solution to lack of water.

Ayala says that in addition to individual rainwater catchment systems, the government could establish areas for rainwater catchment, build infiltrative ditches in mountain hillsides to aid reforestation, and help refill groundwater reserves.

The commission has no immediate plans to introduce a rainwater catchment system at the municipal level, Balbuena says.

Ayala has given private and public workshops — in person and online — in Guerrero on the rainwater catchment system. He says that people can build systems with everything from PVC pipes and galvanized steel to recyclable materials like bamboo or plastic buckets.

“It’s about taking advantage of what’s there,” Ayala says. “There’s a crisis among us humans because we’ve lost the ability to live with nature, and we’ve been abusing it.”

Avigaí Silva is a Global Press Journal reporter based in the Mexican state of Guerrero.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Sarah DeVries, GPJ, translated this article from Spanish.