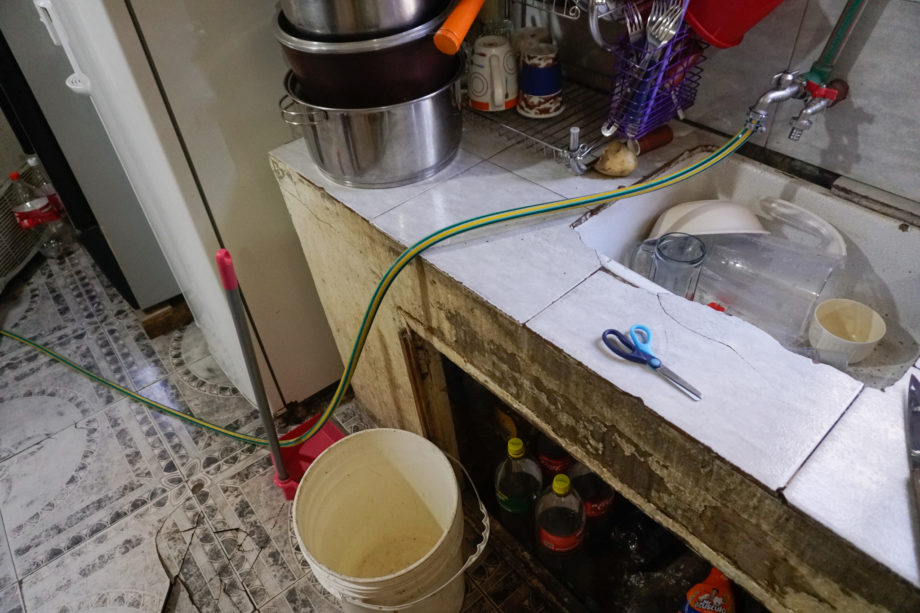

BUENOS AIRES, ARGENTINA — The alarm goes off at 3 a.m. In a room encased in hollow brick walls and a sheet metal roof, the heat stifles. Half asleep, Silvia Canos plugs in a water pump. She presses her ear against the plastic hose and listens for water. Not a single drop slips out. In a few hours, when Canos gets up to go to work, she will not have water to wash her face or make breakfast.

Canos lives in Villa 21-24, a Buenos Aires neighborhood of 10,000 families, and one of the capital’s 57 “barrios populares” — neighborhoods of informal housing in which over half the residents don’t have a title to the land. In these urban settlements, basic infrastructure arrives slowly — or never. Having long lacked access to safe, potable water, these communities face the direst consequences of a warming planet.

This summer, which ran from December 2021 through March 2022, was one of the hottest in Argentina’s history. In January, during a 21-day heat wave, many cities set daily records for minimum temperatures, according to the National Meteorological Service. On Jan. 15, temperatures in Buenos Aires didn’t descend below 30 degrees Celsius (86 degrees Fahrenheit) over a 24-hour period, marking the city’s hottest night since weather record-keeping began in 1906.

“During the summer, hundreds of families like us do not have water,” Canos says. “Over the years it has gotten much more complicated, and now the water we were expecting isn’t coming.” Canos is one of 9 million Argentines whose homes aren’t formally connected to the public water network, having to rely instead on improvised plumbing systems. Of those, at least 3.5 million live, like Canos, in barrios populares. There are at least 4 million people living in these neighborhoods in Argentina, at least 300,000 in the city of Buenos Aires alone.

María Eva Koutsovitis, a civil engineer specializing in hydraulics and coordinator of the Community Engineering Department at the University of Buenos Aires, says do-it-yourself connections aren’t always safe. “When you create suction through a hose that is submerged in soil contaminated with, best case, fecal matter and, worst case, heavy metals, all those [substances] surrounding the hose enter through punctures,” she says.

Koutsovitis conducted a study that showed that in the south of the city of Buenos Aires, which has the highest concentration of barrios populares, infant mortality is twice as high as in wealthier neighborhoods. Access to drinking water is directly related to infant mortality and life expectancy, Koutsovitis says.

In Scapino, a barrio popular of 600 families, resident Liliana Beatriz González Peralta says the water that comes out of her house’s homemade plumbing system is cloudy and smelly. “When I take a shower, my body itches everywhere,” she says. “I take an antihistamine and put alcohol all over my body — there is no other way.” Her 5-year-old daughter has a rash covering her body.

González Peralta says she prefers the water delivered by trucks, a service provided by the city government for select neighborhoods. Every day from Monday to Saturday, a water truck comes to Scapino, and each resident has to carry a heavy hose to their roof to fill up their water tank. But González Peralta isn’t always available. “They bring you water, but they don’t put it in the tank,” González Peralta says. “Sometimes I have a medical consultation, an appointment somewhere.”

María Zorrilla, another Scapino resident, takes turns with her 18-year-old son to wait for the water truck and haul the water. “Most of us here in the neighborhood have that problem,” she says. “If one works, the other can’t, because they have to carry the water.” Her homemade plumbing system, she says, hasn’t worked in two years.

The water truck option isn’t necessarily safe, Koutsovitis says: “With bulk transport, unless you comply with very strict protocols, the safety of the water isn’t guaranteed.”

Water truck or do-it-yourself plumbing, these alternatives mean that at least one family member must dedicate a few hours a day to obtaining water — and that usually falls on women, which limits their access to formal work, Koutsovitis says.

Gabriel Mraida, president of the city’s Housing Institute, the government body responsible for community equipment, infrastructure, utilities and reducing the housing deficit, admits that the water service provided by water trucks is not optimal, but an interim solution. “We are in nine neighborhoods doing the sewers, water, electricity, paving, etc.,” Mraida says. “Around 150,000 families will benefit from the infrastructure work we are carrying out this year.”

Through a spokesperson, the Housing Institute says all of Villa 21-24 is expected to have formal access to the water network by 2024.

Zorrilla and Canos don’t hold much hope that a formal connection to the water network will come soon. “They have been promising that for countless years,” Zorrilla says, referring to the city government. “There have been years of meetings and promise after promise that has not been kept.” She filed her first claim for a formal water connection six years ago, she says.

In the meantime, Zorrilla waits for the water truck. Not far from her house, employees at the Ministry of Human Development and Habitat use a powerful hose to clean the sidewalks.

Lucila Pellettieri is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Shannon Kirby, GPJ, translated this story from Spanish.