An Illustrated Guide to Zimbabwe’s Changing Currency

CAST OF CHARACTERS

The Zimbabwean Government (first frame)

Banks (second frame)

Citizens (third frame)

KEY

Orange: Inflation rates rise; Zimbabwe uses its own currency or currencies

Green: Inflation rates stabilize or decrease; Zimbabwe uses foreign currencies

Illustrations by Matt Haney for Global Press Journal

2003-2006

Controversial land-reform policies and inflation are the talk of the country. As inflation spikes, the cost of printing money soon outweighs the value of the currency. The bearer cheque, a stop-gap currency printed on cheaper paper, emerges. To boost consumer confidence, the government offers a temporary solution: a new version of the country’s dollar with three zeros knocked off. Inflation rises by a factor of 1000. The trick didn’t work. Prices continue to rise.

“We were printing money unashamedly by that time. They just thought it would be prudent to remove the three zeros and that would make it a functional currency,” says Nigel Chanakira, a local businessman and co-founder of Kingdom Bank.

2008

A new year, a new Zimbabwean dollar. This time inflated by a factor of 10 billion, these bills replace those issued in 2006. By midyear, inflation hits 89.7 sextillion percent. A $100 trillion note doesn’t cover a bus fare.

“All of us were trillionaires and billionaires who could not even buy two bottles of soda,” says Tendai Biti, a member of parliament, recalling 2008.

2009

In response, the government announces a multi-currency system that allows U.S. dollars, South African rand and a host of other currencies to be legal tender. Now virtually worthless, the Zimbabwe dollar goes out of circulation.

“[U.S. dollars] stabilized the economy. Goods could be found in the supermarket, and services were restored,” remembers Ithiel Munyaradzi Mavesere, an economics lecturer at the University of Zimbabwe.

2009-2013

With a host of currencies and a new government that shares power between the longtime ruling party, ZANU-PF, and the opposition party, MDC, Zimbabwe’s economy grows.

But as the U.S. dollar becomes the de facto currency, a parallel market grows too. The Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe struggles to control the currency supply.

2013

After 33 years in power, President Robert Mugabe is re-elected amid controversy and his party, ZANU-PF, wins a strong parliamentary majority, which effectively ends the power-sharing government. The multi-currency system remains, but public debt skyrockets and the country’s economic growth quickly reverses.

With no support to continue issuing its own currency, the central bank prints billions of short-term securities called treasury bills.

2014-2015

U.S. dollars are still the country’s primary currency, but they become hard to find. With no way to control the number of bills coming into the country, a currency shortage takes hold.

In response, the Zimbabwean government introduces $10 million USD worth of bond coins, another new currency. The coins are backed by a loan from the African Export-Import Bank.

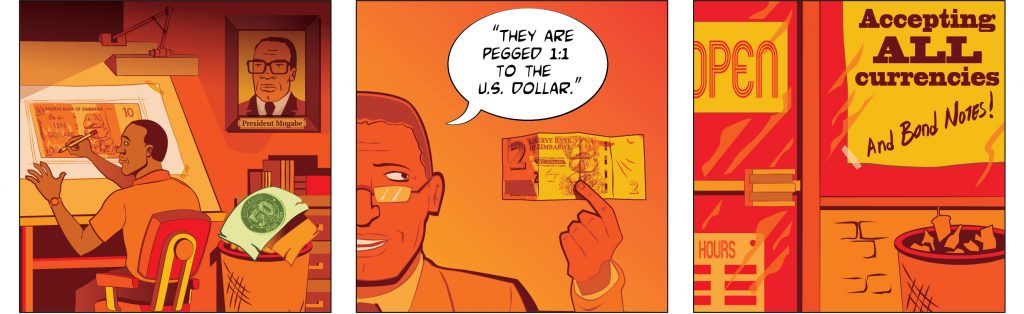

2016

To ease the shortage, the government prints another new currency, bond notes, which only has value in Zimbabwe. Its value is supposed to match the U.S. dollar, but international economists don’t agree. The black market for foreign currency booms.

“In retrospect it looks like a con job,” Chanakira says. “It was like a back-door introduction of our own currency.”

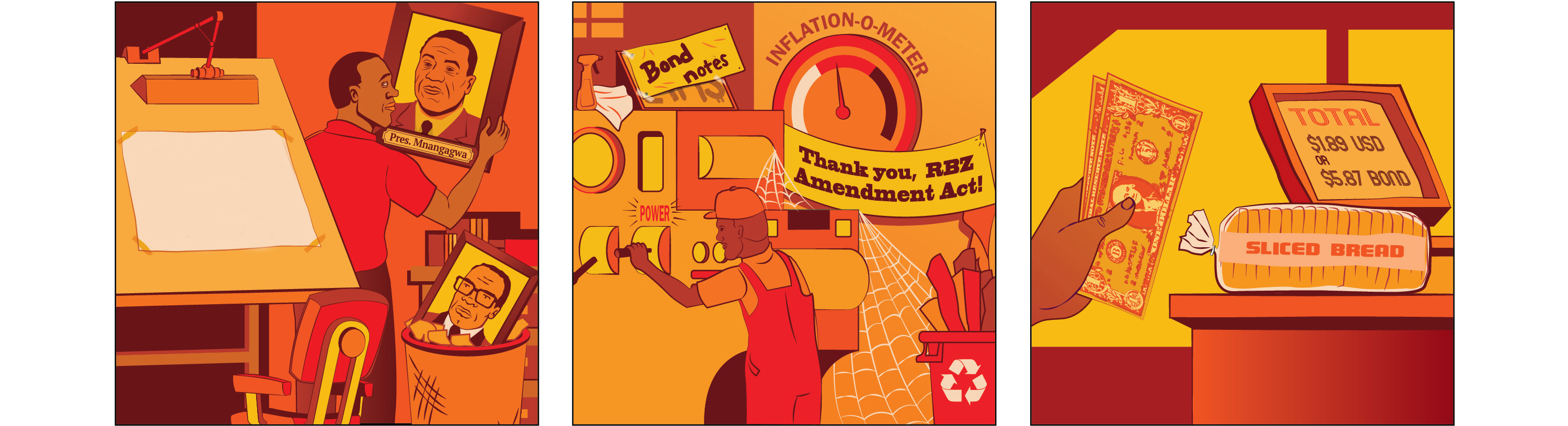

2017

The country’s recently dismissed vice president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, orchestrates a military takeover. Political turmoil grips the nation as Mugabe is pushed from power.

Parliament passes one of several Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) Amendment Acts, which allows the central bank to print and issue bond notes with abandon.

“The central bank went on an overdrive in printing the bond note,” Mavesere recalls.

2018

In October, without warning, Zimbabweans with U.S. dollars in their bank accounts awake to the surprise that their dollars were replaced with a currency called RTGS, which are described as digital bond notes. The true value of RTGS plummets, despite claims that their value was equal to the U.S. dollar. People with U.S. dollars in their accounts lose the majority of their savings. And consumer prices shoot up fivefold. The consequence is a total loss of confidence in the banks.

“Let’s take our money out of savings, let’s keep it under the pillow,” says Chanakira.

2019

In February, RTGS is introduced as a formal currency, now called the RTGS dollar, with the admission that its value isn’t equal to the U.S. dollar. On June 24, the government renames the RTGS dollar again, calling it the Zimbabwean dollar. But this time, the new currency isn’t really new at all. With no resources to print money with a new design, the Zimbabwean dollar is just a bond note.

In June, foreign currency is outlawed, with a few exceptions – to purchase luxury goods, for example. But luxury isn’t top of mind for most Zimbabweans, who again find themselves in the grips of inflation. In August, the government stops publishing inflation rates, after the official year-on-year rate exceeds 175 percent.

The Future

New bills and coins with a subtle new design debuted today. The name and design may be new, but the value remains as uncertain as ever.