Noella Nyirabihogo, GPJ DRC

Therese Chikuru sells a sorghum-based drink, known locally as musururu, at a camp for displaced people in Kanyaruchinya, Democratic Republic of Congo. Chikuru and her six children fled fighting in Bunagana, DRC, between government forces and the armed group M23.

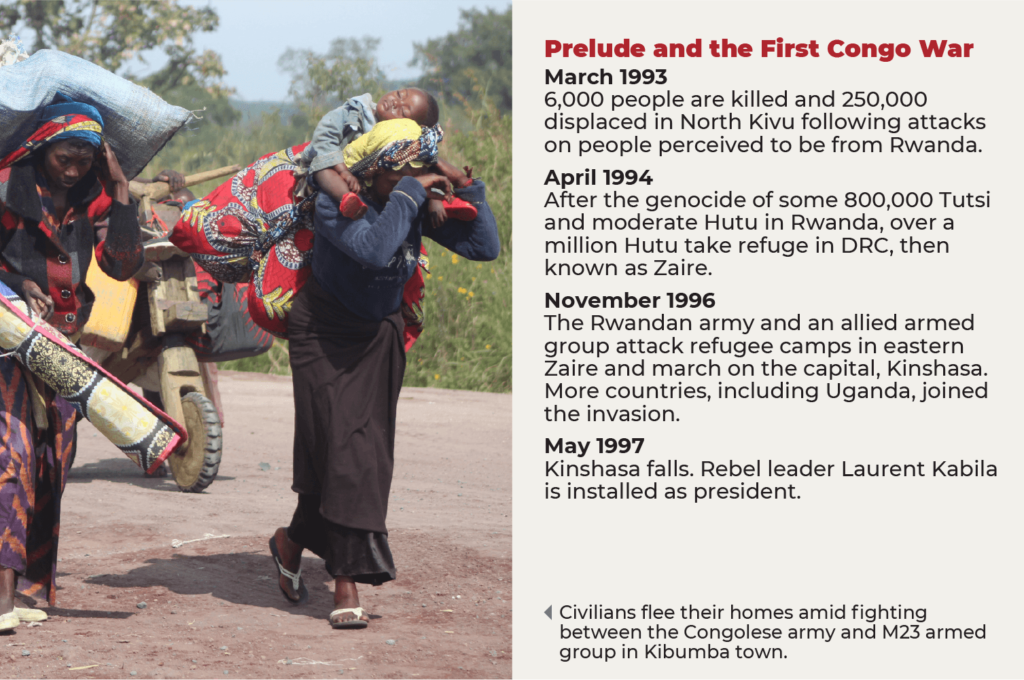

KANYARUCHINYA, DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO — They heard the crackle of gunfire, and immediately fled. The people of Rutshuru territory had little choice — their villages, scattered outposts of bean, maize and banana fields in the country’s east, had turned into battlegrounds. Many villagers ducked under the green, leafy canopy the banana stalks provided, listening for a stretch of silence that would allow them to escape. When it came, they grabbed what they could — money, blankets, maybe a goat — and walked for hours and hours.

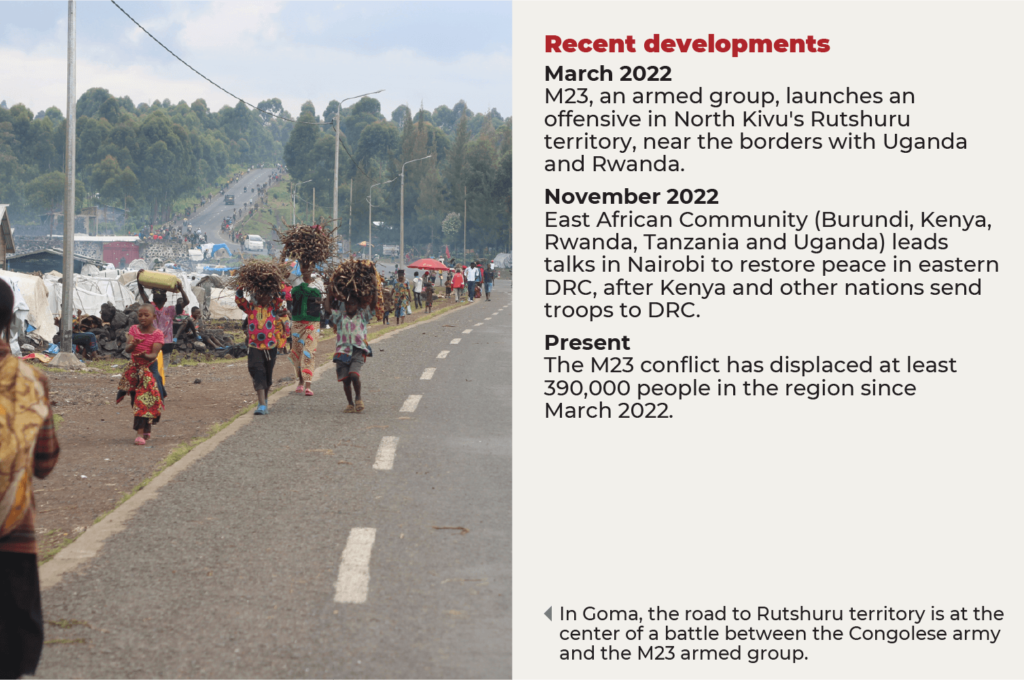

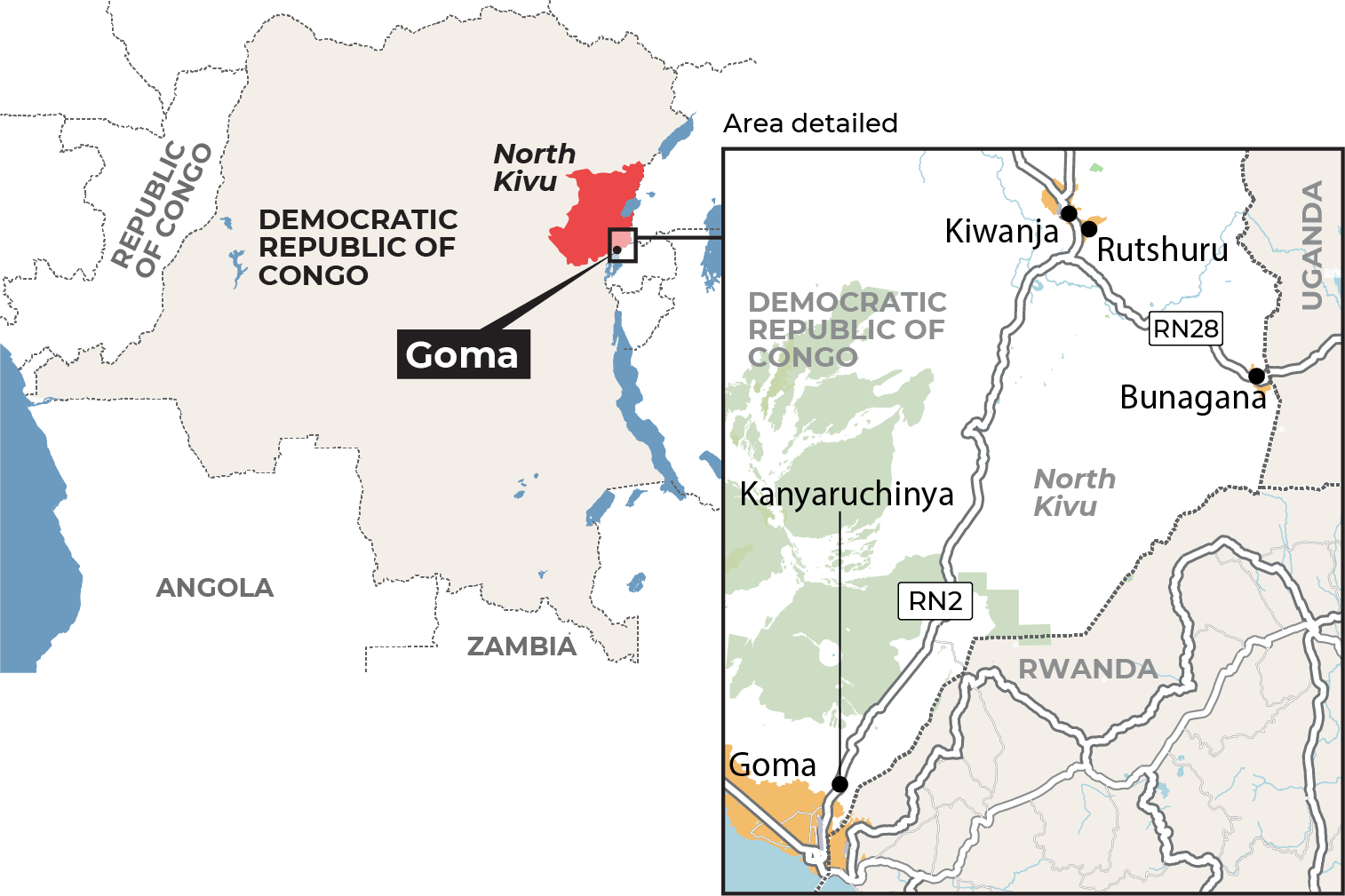

The villagers ended up at a displacement camp the government set up in Kanyaruchinya, a few kilometers from Goma, the capital of North Kivu province. Families slept in classrooms or in a camp-issued white tarpaulin tent measuring 4 meters by 2 meters (13 feet by 6.5 feet), which they pitched wherever they could find space. They believed they wouldn’t stay long — that government forces would soon expel M23, the armed group that seized Rutshuru. That was months ago. Thousands of people, many of them children, remain trapped in an earthly purgatory: The camp lacks food, clean water, toilets and schooling, but home is a war zone.

Ernestine Ombeni, 48, sits on a classroom floor with her daughters, ages 12 and 10, who are visibly weak and hungry. They sleep at a school, and every morning at 4, when the sun has yet to rise and the birds are still sleeping, they wake up and rush out of the building before students arrive. It’s this, or the specter of combat. “The bullets won’t choose who to kill or spare,” Ombeni says, her voice shy, her eyes empty. “Many civilians, including my friends and family, have died in the fighting. At this point, it is not safe for my family to return.”

Most M23 members are Congolese Tutsis who claim they are protecting their brethren in North Kivu, which borders Rwanda and Uganda, from Hutu groups. “This is our homeland, and we will never cede any part of our territory,” Willy Ngoma, the group’s spokesperson, tells Global Press Journal. Starting in the mid-aughts, the group’s predecessors cycled through several bouts of warring and peacemaking with the DRC government. (M23, or the March 23 Movement, refers to the date of one ceasefire agreement.) However, until recently, the rebellion had been dormant for years.

M23’s resurgence is likely linked to long-standing tensions between Rwanda and Uganda, according to an analysis by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, a think tank affiliated with the United States Department of Defense, with rival state-backed groups clashing over Congolese gold, diamonds and coltan, a key element of electronic devices. DRC officials have accused Rwanda of arming M23. In recent months, the group has captured the towns of Bunagana, Rutshuru and Kiwanja, and displaced hundreds of thousands of people. Many are languishing in camps in DRC and Uganda — if they make it there. Theo Musukula, who oversees the Kanyaruchinya site, says more than 30 recently arrived children died due to exhaustion and trauma.

At the camp, older men and women, used to working in the fields, sit on mats and talk about anything and everything to kill time. Good Samaritans arrive with beans, fufu and vegetables, and smoke from cooking fires hovers above, but there’s still never enough to eat, as more displaced people straggle in by the day. People frequently trudge the 7 kilometers (4 miles) to Goma, rain lashing their faces, to beg for money, food, clothes, pots and blankets. “I feel so worthless and useless here in the camp. I watch my children starve, and there’s nothing I can do to help them,” Ombeni says. She has five kids, all younger than 16. “We don’t have our own farmland here, and it’s also impossible to find a job. So all we can do is beg on the streets.”

Home doesn’t seem much safer. In July 2022, Human Rights Watch, a New York-based nonprofit that investigates abuses around the globe, reported that M23 had executed more than two dozen civilians they claimed had colluded with Congolese forces. One woman said M23 fighters dragged her father out of his home, screaming, “It’s you who told the military where we were hiding!” She heard gunshots, went outside and saw his dead body on the ground, hands bound. Ngoma, the M23 spokesperson, categorically denies the allegations in an interview. “These accusations are unfounded and solely aimed at damaging our reputation. This is our home, and we would never kill our own brothers and sisters. We’re here to protect them,” he says. In fact, Ngoma encourages displaced villagers to return. “We welcome whoever wishes to come back and want people to know that we’re here to keep them safe.”

Ombeni’s 96-year-old grandmother was too weak to leave her home and remains in M23-occupied Bunagana, on the lower end of North Kivu, near the Ugandan border. Two of her daughters stayed to take care of her. (Their names are being withheld to protect their safety.) In a phone interview, one daughter says the largest change under M23 was a temporary border closure, snuffing out the small-scale trade of sugar, maize flour, vegetable oil and rice that many locals rely on. “Today, life is very uncertain from an economic point of view, so the town doesn’t move like it used to,” she says. “There are few people; some stores are still closed because there is no traffic like before.” However, she says, the gunfire has died down.

Bullets are not the only dangers, though. Jean Baptiste Batumike, 51, escaped Rutshuru months ago with his wife and their five children. He spends his days wandering the Kanyaruchinya camp, unable to do anything to support them. At night, they squeeze into their tent and pray it doesn’t storm, as rain will flood the tent, soak their blankets and force them to haul everything to drier ground. But if they went home, he says, Congolese forces might brand them as “traitors” sympathetic to the armed group, which carries its own risks. Not long ago, his cousin chose to stay in his village instead of fleeing gunfire. Government forces accused him of being an M23 scout. He was not, Batumike says. “Today, he is languishing in a prison, where his only crime was to stay in his compound with his cattle because he was tired of running away every day.”

People stranded in the camps have repeatedly staged protests to demand the government dislodge M23 from their homes. Last year, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi asked fellow members of a regional economic coalition, the East African Community, to help quell the violence. Kenya and other countries have sent troops, and peace talks are ongoing; M23 recently announced it gave up two locations it had seized. Gen. Sylvain Ekenge, commander of the communication and information service of the Congolese army, says, “I assure you that not a single centimeter of our country will be left under the thumb of the M23.”

Meanwhile, lives molder. Pierre Tumaini and his wife sit on the steps of the school where, at night, they curl on the hard floor and try to sleep. They abandoned their crops and livestock in Bunagana months ago and, with their seven children, slogged to Kanyaruchinya. Tumaini is 61, his hair salted by time, his voice quiet but desperate. “Not only have I lost my lands to the war, but I’ve also lost my dignity,” he says. “My children, my sons- and daughters-in-law, and I are forced to sleep on the floor of this classroom. Even farm animals sleep in better conditions than we do.” Yet, hope remains. Most people at the camp wear T-shirts or casual dresses to withstand the dust and muck. Tumaini clothes himself in a reminder of home: a black business suit.

Noella Nyirabihogo is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Emeline Berg, GPJ, translated this article from French.