SUDURPASCHIM, NEPAL — Earlier this year, at the beginning of March, Sirjana woke up with a bad stomachache. It was near midnight, and the village — clusters of houses, about four dozen or so, sprinkled on the side of a hill, separated by terraced fields — was still. As per custom, the toilet was located outside the house, so she drowsily stumbled out of bed to use it. That’s when she realized she’d started her period. She froze, unable to re-enter her house.

Sirjana, 20, is soft-spoken but articulate, a student of business management. (Fearing retribution, she asked to be identified only by her first name.) One day, she says, she hopes to work for the betterment of society. But there is one battle within her own home that she has not yet been able to win: her family’s insistence on observing “chhaupadi,” a longstanding practice of banishing menstruating girls and women to outdoor sheds because they are considered impure.

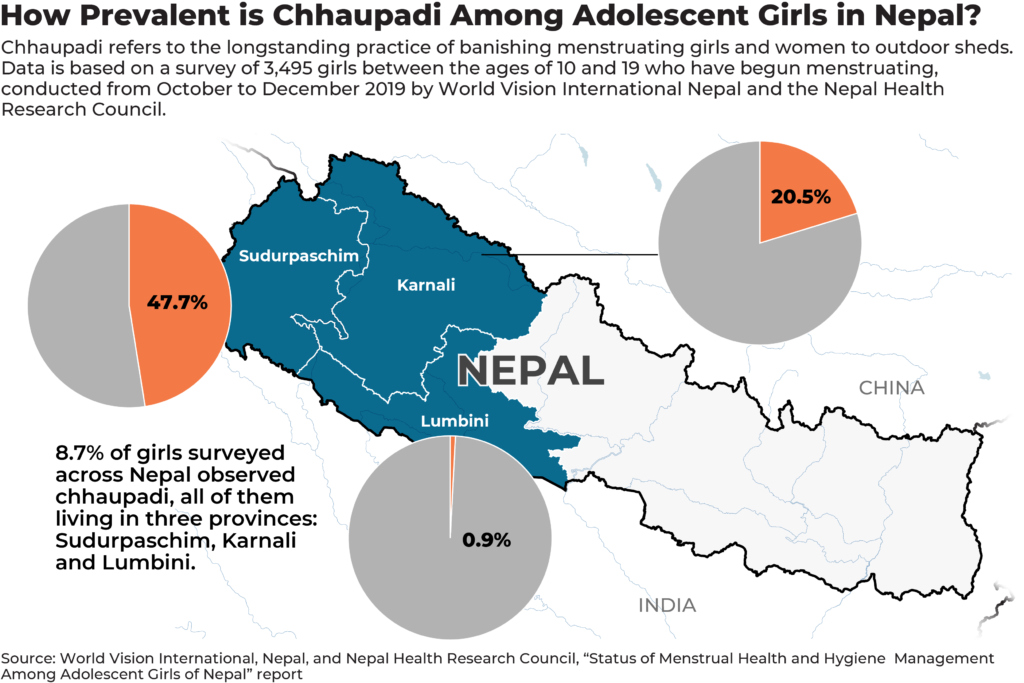

Nepal’s highest court outlawed the practice in 2005. But chhaupadi persisted, in part because there was no enforcement mechanism. Only about half of people in Sudurpaschim province, in the far west of Nepal, knew that the practice was illegal, according to a 2020 survey conducted by World Vision International, a humanitarian aid group, with the Nepal Health Research Council, a government agency.

In August 2017, the government introduced penalties — three months in jail or a fine of 3,000 Nepalese rupees ($24) — for anyone forcing a family member to sleep outside while on her period, or discriminating against her in general. To date, nine cases have been filed under this law nationwide, five of them in Achham district, where Sirjana’s village is located. Sirjana’s experience, however, highlights the limits of state intervention in stamping out the custom.

On that March night, Sirjana stood outside the house for half an hour, calling out to her family. No one seemed to hear her. “I was crying because I was in pain,” she says. Finally, her mother came out to hand her a change of clothes. Sirjana then went to sleep in the cramped, lightless shed next to the house, on a stack of hay with a thin blanket made from old clothes. She remembers thinking to herself, “I have to bear this because I am a girl.”

***

The first time Sirjana got her period, she was in school. When she came home to change, her family wouldn’t let her enter the house. “That was the first time I slept alone,” she says. She was 14. “I was very scared at night.”

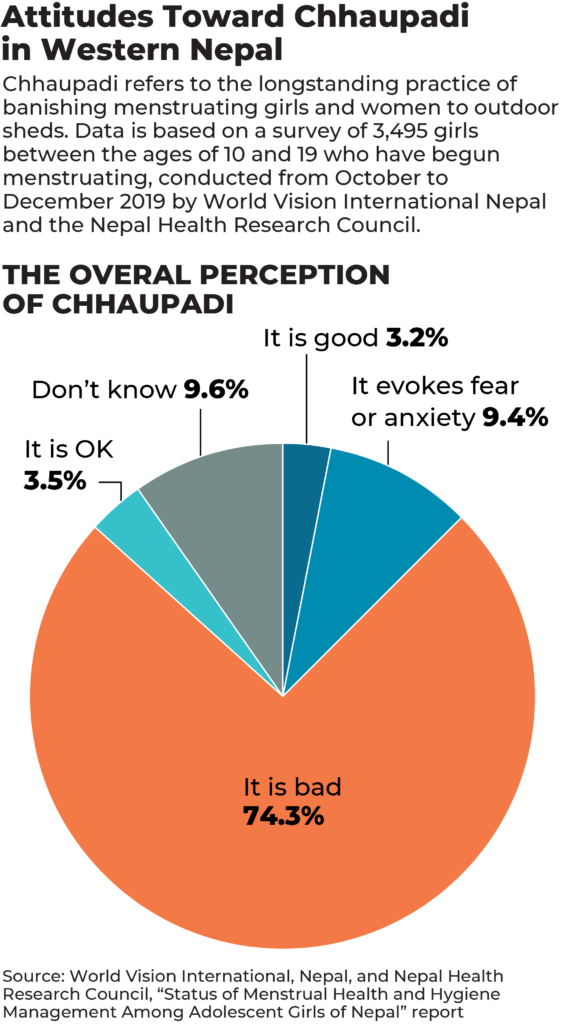

Menstrual taboos, predicated on the idea that women on their period are dirty or impure, persist in many cultures, but the practice of chhaupadi — in Nepali, chhau means “menstruation” and padi means “a place to stay” — is mostly prevalent in the western part of Nepal. According to the 2020 survey, 8.7% of adolescent girls nationwide still practice chhaupadi, nearly half of them hailing from Sudurpaschim province.

From time to time, reports emerge of women dying while practicing chhaupadi: from snake bites, hypothermia, or smoke inhalation from fires that they build to keep themselves warm. Staying alone in huts also makes women more vulnerable to sexual exploitation, observers note. Nepalese police say 12 people have been injured or killed while observing chhaupadi since mid-2015 whereas according to local officials, Achham district alone has a record of 13 deaths over the past decade and a half.

Sirjana’s life changed in many ways after she got her period. Menstruating women are not allowed near the main water supply — the gods will get angry and the water will dry up, according to superstition — so the village has a separate tap for them. “It is about 25 minutes from my house and you have to wait in line for your turn,” Sirjana says. Another, for drinking water, is a further 15 minutes away. Sirjana would wake up early in order to bathe and wash her clothes. Then she would walk to school — another hour away.

Her studies suffered, too. “There was no time, and no light to study,” in the hut, she says. “So I never did my homework while I was menstruating.”

This is common, says Lal Chandra Jaisi, principal at a local school. “Girls practicing chhaupadi do not do their homework. They don’t say why, but give other excuses. When they are young, they’re good at studies; but when they get older, they become weaker and score lower marks.”

Jaisi insists that things are changing, albeit slowly. “Before, girls wouldn’t come to school when they were menstruating,” he says. “Now, they come regularly.”

Sirjana’s grandmother, Champa, is 65 years old but has the hectic demeanor of a younger woman. (She too asked to be identified only by her first name for fear of retribution.) In her view, a lot has changed already. When she was a girl, she had to observe chhaupadi for seven days, rather than four or five. There were no huts to live in — menstruating women slept in the fields and when it rained, they would huddle inside a makeshift tent. Sirjana and Champa have a loving relationship — as they talk, they exchange smiles — but on the matter of chhaupadi, they can’t see eye to eye.

Champa is adamant that if chhaupadi isn’t practiced, bad luck will befall the family. The house will shake or catch fire. Cows and buffaloes will stop giving milk. Marriages will fall apart.

“God will get angry and we will get sick,” Champa says. “This is why we continue the practice.” She remembers the house shaking once; another time, after a menstruating woman touched the house, a tiger stole a goat.

One limitation of the law is that chhaupadi is often enforced by close family members — 71% of practicing adolescent girls say they do so out of family obligation; less than 14% due to their own belief in divine retribution — and women are unlikely to file a police complaint against their own relatives.

Later, when her grandmother is out of earshot, Sirjana recounts her struggles. “I am against chhaupadi and fought with my family many times. But I couldn’t convince them. They have been practicing it for generations.”

In 2017, after penalties were introduced, Sirjana’s family destroyed the original hut they had long used for the practice, located a few minutes away from their house. Hope flickered within Sirjana. But the family promptly constructed another hut, this time right next to the house. This way, they thought, their daughters would be safer — after all, they too were troubled by reports of girls dying — but the practice would also continue.

“The government is destroying the physical sheds, but not the practice,” Sirjana says. “They were unsuccessful in destroying the sheds from people’s hearts. They made a law which is only on paper.”

***

“We are the first to declare our municipality free of menstrual sheds and huts,” says Bhumisharan Dhakal Bajgai, deputy mayor of Kamalbazar municipality in Achham district, near Sirjana’s village. Bajgai, who talks swiftly and decisively, practiced chhaupadi when she was younger — the school she attended had a temple on the grounds, so teachers and students would miss school when they were menstruating. Things are different at the school now, she says. Although women and girls still don’t enter the temple when they’re on their period, they do come to class. As for Bajgai, she doesn’t observe the practice at all anymore.

In 2020, the local government launched a full-fledged campaign against the practice, ordering the destruction of sheds and huts. Police and ward officials went to villages, removing roofs, kicking out doors, and wrenching out window frames. “In 2020, we destroyed 150 menstrual sheds and huts,” Bajgai says. The system of separate water taps for menstruating women, however, has mostly remained intact in the region.

The idea behind the state action, which mainly took place in Sudurpaschim and Karnali, was to make the huts uninhabitable, and therefore useless. “But people made them again,” says Meera Dhungana, senior legal adviser at the Kathmandu-based Forum for Women, Law and Development, a nongovernmental organization, who worked on the legal challenge that resulted in the 2005 verdict banning chhaupadi. Anita Neupane Thapalia, a lawyer working since 2004 to end the practice, says some families have disguised their rebuilt sheds as small shops; other women, Dhungana says, had to stay outside in huts without roofs.

“They get sick and catch pneumonia,” Thapalia says. “Some take medicine in order to not menstruate because they don’t want to stay in sheds. This affects their reproductive health.”

In some instances, destroying the huts made conditions even more unsafe for women. And while others aren’t banished outdoors, they are still treated as pariahs in their homes, restricted to a room and forced to walk long distances to drink water and bathe.

“The practice will not end just by destroying huts,” Dhungana says. “The attitude should change first. There should be no discrimination or untouchability against women. It is a human right. Women and girls are humans.”

To enforce the ban, some municipal officials have resorted to threatening to withhold state benefits from families that remain intransigent. As for Bajgai, whenever she is out on an official visit, she keeps her eyes peeled for menstrual huts and, while giving speeches, always advises her constituents to give up the custom. “The Nepal government should make a detailed policy against chhaupadi,” she says, “and we will follow it to end the practice.”

“It is easier to change the law. But it is difficult to change the culture,” says Fanindra Mani Pokharel, spokesperson for the Ministry of Home Affairs. Menstrual huts continue to be destroyed in the provinces of Sudurpaschim and Karnali, he says.

“Social change is happening slowly,” he adds. “It will take a long time.”

***

In late February, nearly 17 years after chhaupadi was first outlawed, Nira Bista stood at the entrance of a primary school in Bajura district, where she’s taught for 12 years. There are no proper roads leading up to it — every morning, Bista walks for almost two hours and scales a steep hill. The school, which offers classes up to third grade taught by three teachers, consists of a handful of rooms and a small front yard. There is no temple within the school but there is one nearby, so the grounds are considered holy. In all her years teaching, Bista had never once set foot on the premises while she was on her period.

Earlier that month, however, local newspapers had caught wind that teachers at the school were still practicing chhaupadi. This brought matters to a head.

That February day, many others from the village trekked up to the school alongside Bista. Shamans performed a puja, a religious ceremony. “We prayed and asked the gods for permission to enter the school,” she recalls. The community knew the old ways could no longer continue — but if change was imminent, it would be ushered in with great care.

The shamans concluded the puja. Then, bravely, tentatively, Bista and the other teacher stepped inside.

LANGUAGE NOTE

Shilu Manandhar, GPJ, translated interviews from Nepali.

EDITORIAL TEAM

Alizeh Kohari, Editor

Jennifer Kennedy, Fact-Checker

Melissa Slager, Copy Editor

Matt Haney, Graphics Editor

Charlotte Kesl, Senior Photo Editor