Illustration by Emilie Maino

OAXACA DE JUÁREZ, MEXICO — Dawn lights up shards of glass along the downtown streets of Oaxaca de Juárez — vestiges of the broken windows of cars that had been parked there during the night.

One evening, upon leaving a dinner event, Sabrina Espinoza discovered her car with two broken windows, and without the cellphone she had left in the glove compartment. Her mind clouded over. She asked herself, “How could they have possibly known there was a cellphone there?” While she and her friends took stock of the incident, two police officers on motorcycles approached and explained, “They’re breaking windows. They use an application to detect devices like cellphones, computers, and cameras that people leave in their cars.” They also told Espinoza that she had to report the incident to the public prosecutor’s office, then left her alone with her thoughts.

But Espinoza decided not to risk going by herself or with one of her friends to file a report. For one thing, she didn’t know either the address of the nearest public prosecutor’s office or the procedure for filing a report. For another, she felt unsafe going to a place she didn’t know at 2 a.m.

Angel Serrano, an expert on security and justice in Mexico, explains that people often think that all that is needed to file a report is for a police officer to come to the scene of the incident and open a report. But that’s not the case. “Filing a report in Mexico is very complicated. It is imperative to do it before an official of the public prosecutor’s office, inside their facilities,” he says.

Most crimes committed in Mexico go unreported; people have low levels of trust in the justice system. Experts and academics are studying this situation so they can propose tools to lower the high rates of impunity in the country.

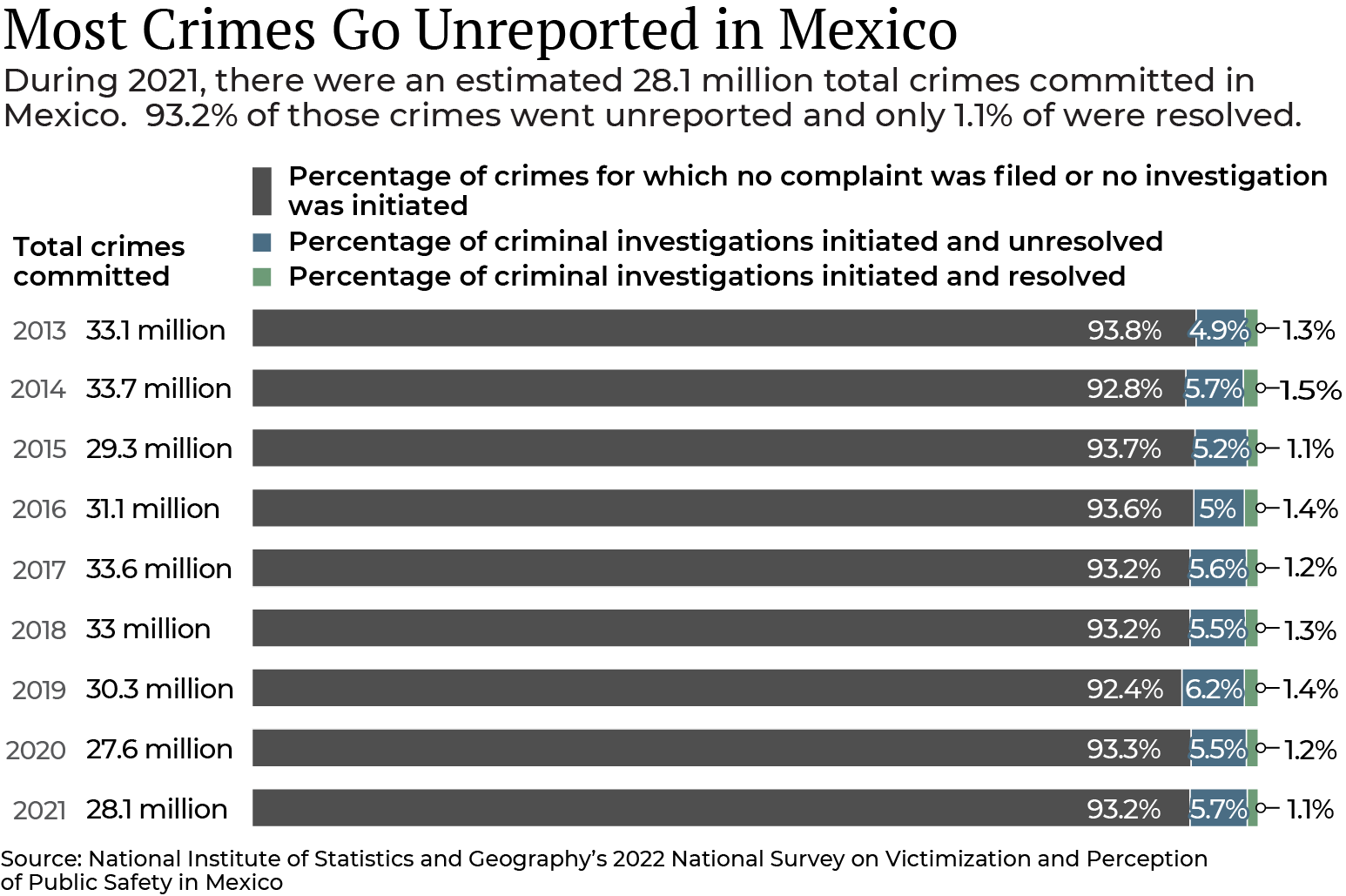

To grasp the quantity of unreported crimes, many countries began to conduct victimization surveys in the 1970s. In Mexico, the National Institute of Statistics and Geography conducted its first such survey in 2011.

The term “dark figure” refers to the total number of unreported crimes — the crimes that have remained invisible, that are not found in the records of prosecutors’ offices. The data is vital to inform public policy on security issues.

The results of the most recent victimization survey, called the National Survey on Victimization and Perception of Public Safety, conducted by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography in 2022, revealed that 93.2% of the crimes committed in Mexico in 2021 were either not reported or an investigation was not opened. Only 1.1% of crimes committed in the country were reported, investigated, and resolved.

Irene Tello, who at the time of the interview was director of Impunidad Cero, a civic organization that studies impunity in Mexico, explains, “We have very good laws, but they are not being applied. And when there is a crime, either the people do not report it, or when they do report it, the authorities do not follow up on the investigation files. And in the end, we end up having this feeling that committing a crime in this country can happen, and there are no consequences.”

It is a circle that goes unbroken, between the unpunished crimes and the millions who do not report them, to create the high rate of impunity in the country, Tello says.

Lorena Castellanos was robbed on a street near the wholesale market in the city of Oaxaca de Juárez. The assailants stole her money and a cellphone that she has not been able to replace — but she didn’t report it. “Why would I report it? If nothing is going to change, no one is going to return my money or cellphone, nor will they look for the people who robbed me, I would only be wasting my time,” she says.

Tello explains that the lack of credibility people give to the justice system is an issue of strategy and will on the part of authorities. “The signals the state does and does not send from its penal system are very important. If you investigate a case very well and resolve it, you send a very clear signal that this is not permitted, and you build confidence in people, so they come in to file reports.”

Ana Fátima López, an attorney who provides pro bono counsel to women who have experienced violence, says, “This level of dissatisfaction and bitterness, of seeing that it does not matter what you do, you feel as though you don’t matter to the authorities … of course it’s discouraging.”

López explains that her relationship with the justice system is tempestuous. “I promote it a lot, but it pains me, knowing that they might go up to eight hours without being seen in the justice centers. But if 1 out of 6 women comes out with a protective order after I’ve suggested they go, I know she has a tool that can serve her in the future.”

Ita Bico Cruz is an advocate at the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman of Oaxaca, an autonomous government agency, where she specializes in gender equity and assists women who have been in violent situations. She says it’s become normal for people to encounter doubt and discouragement when they go to the public prosecutors’ offices to file reports.

“It can seem like they do not want people to file a report because of the mistreatment they receive. When the person who files a report is treated poorly or when their information is doubted, they are being revictimized,” she says. This means the person is being made to relive a traumatic situation instead of receiving concrete and caring support that could facilitate the investigation, she adds.

Even for those who do file a report, information on the progress of the investigation is out of reach, Serrano points out. “They give you an investigation file number, but there are no mechanisms for following up on it, for finding out the status of the investigation, if anyone has been detained or not. It is very complicated for people to be able to access all that information,” he says.

“Law enforcement is the bottleneck in the fight against impunity,” explains Impunidad Cero in its 2021 report on the State Performance Index of Attorney Generals’ Offices, an analysis the organization has conducted annually since 2017.

The justice system is composed of two large pillars: law enforcement (two types of attorney generals’ offices: procuradurías or fiscalías) and administration (judges and magistrates). But other elements also exist, such as mediation and alternative means for resolving conflicts.

The factors affecting law enforcement performance, according to the Impunidad Cero report, range from the reduced number of personnel in public prosecutors’ offices per 100,000 inhabitants to the ways in which state attorneys general are elected (the Fiscalía, or office of the state attorney general, is the institution that directs and organizes the state-level public prosecutors’ offices, called Ministerios Públicos). For the most part, state attorneys general are appointed by governors and local congresses, “opening up the possibility for the executive branch to intervene directly in the decisions of the state attorney generals’ offices, which are supposed to be autonomous agencies to avoid any type of corruption and impunity,” Tello explains.

In August 2022, the previous state attorney general, Arturo Peimbert, in a hearing before the State Congress of Oaxaca, explained that the law enforcement backlog was inherited, which rendered his efforts in a year and a half in his position insufficient. In his view, the path to transformation remains long and the terrain rough because the dysfunction comes from decades in which the justice system has been utilized to keep in power those already in power. “The judicial system has not been an instrument of justice but an instrument of political and economic power,” he said.

Peimbert, who headed the Office of the Human Rights Ombudsman of Oaxaca before becoming state attorney general, explains that from that position, he was able to begin diagnosing the situation with the office of the state attorney general through various investigations. The ombudsman’s office ultimately issued 15 recommendations. The investigations revealed fundamental problems, such as “inactivity of public prosecutor office personnel during criminal investigations; lack of legal technique and judgment when resolving investigations for which the public prosecutor’s office was responsible, resulting in failure to execute criminal proceedings; abuse of power by personnel of the same office of the state attorney general; lack of legal knowledge for the integration of investigation files, among others.”

Olga Sánchez Cordero, a senator, president of the Senate Justice Committee and former interior minister and Supreme Court minister, thinks that, to eradicate the vices stymieing law enforcement, two changes are critical: “for there to be job security for those serving in law enforcement and for their pay to be at the level of those who impart justice, which is much higher.”

Former State Attorney General Peimbert emphasizes the need for autonomy at the office of the state attorney general. “In the administrative sphere, the budget is implemented through the Finance Ministry, which can clearly become a control mechanism when most of the workers in direct or indirect contact with the cases being investigated and with criminal prosecution are actually employed by the Ministry of Administration,” he says.

He also points out that, of the 1,109 people who are officially counted as state investigation officials, only about 600 are active as operating staff. The rest are either administrative staff or they appear on the payroll because they have not received a pension.

For Tello, filing a report is the tool citizens possess to raise awareness of crimes and the means by which civil society can lower the high levels of impunity in the country. “We do not want to go around everywhere saying, ‘File a report.’ But if a person wants to do it, we created the website denuncia.org. It uses simple language, and people can review information on everything from where to find all the public prosecutors’ offices in the country and what information to bring with you when filing a report, to how to follow up on your investigation, what irregularities can occur and how to avoid them, and direct hyperlinks to the state attorney generals’ offices by state, plus more.”

Various states have now created webpages to file initial reports online, but even after doing that, there is still a requirement to go to the public prosecutor’s office, Tello explains.

Impunidad Cero launched denuncia.org in October 2020, and as of this past October, two years since its creation, the number of visits was 686,612, with an average of 940 visits per day.

Adriana Romo is a psychologist and founder of Red de Mujeres de La Laguna, an organization that supports women who have experienced violence. She explains that they have downloaded the guides that Impunidad Cero makes available online so they can navigate the system when accompanying women to file reports.

“We went with a woman to file a report at the public prosecutor’s office, and while she was filing, we were able to ask the official at the public prosecutor’s office not to open a new file but to add on to an existing file because this was not the first time she was filing the same report,” Romo says. “It was thanks to the guides that we understood the office had the obligation to add the reports together to ensure the investigations have continuity, and not to enter a report as if it were the first one.”

Ena Aguilar Peláez is a Global Press Journal reporter based in Oaxaca, Mexico.

TRANSLATION NOTE

Shannon Kirby, GPJ, translated this article from Spanish.